Hardspace: Shipbreaker – How It Evolved From Game Jam Experiment, to Game Pass Gem, to New Game Series

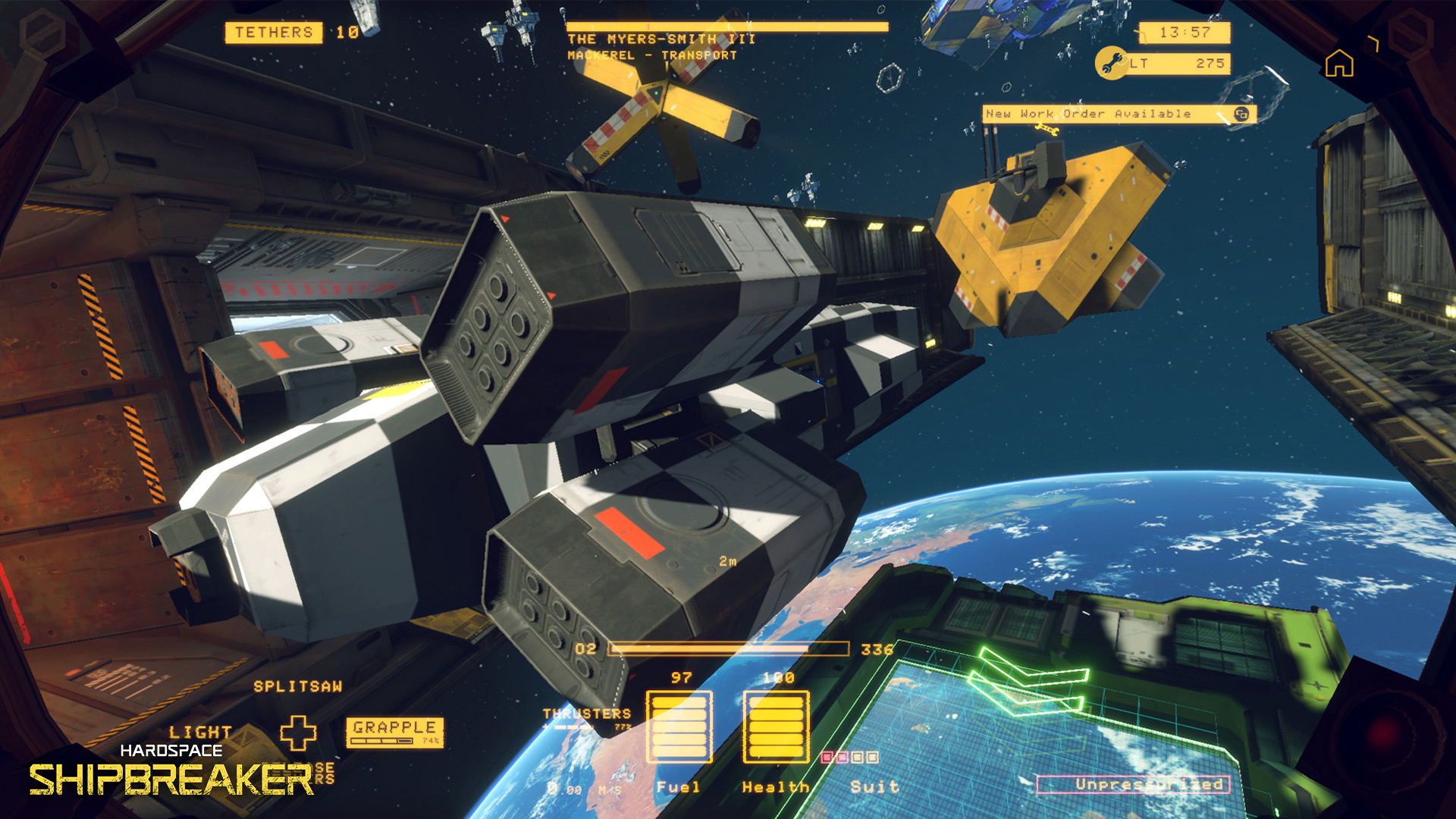

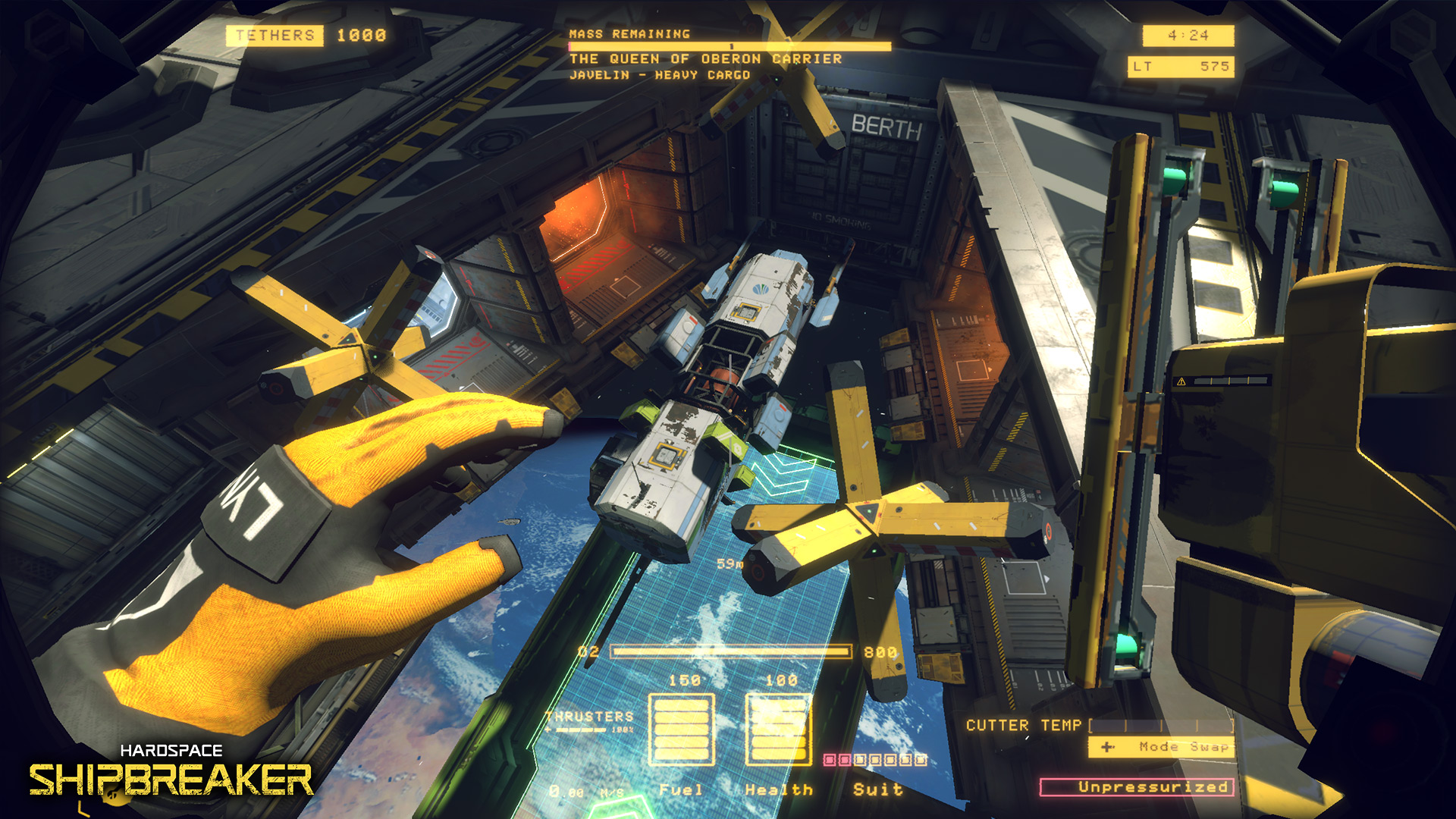

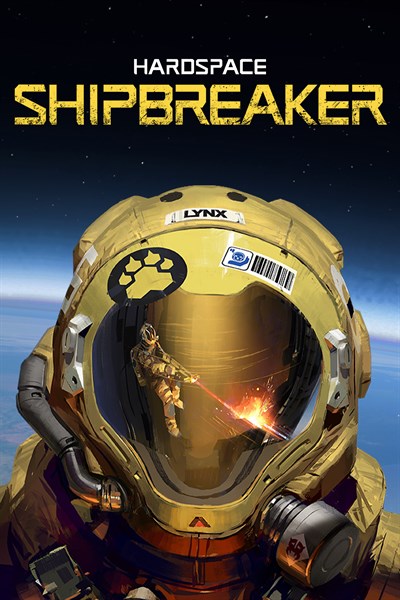

Hardspace: Shipbreaker is that very rare thing: a video game that feels almost wholly unique. It may have the visual trappings of a first-person shooter – a HUD, a radial menu stuffed with equipment, a health bar – but simply playing the tutorial shows you how truly different this game is. After putting dozens of hours into the Shipbreaker salvaging yard, I became convinced that this is one of the most intriguing, beguiling, relaxing and testing experiences available in Xbox Game Pass.

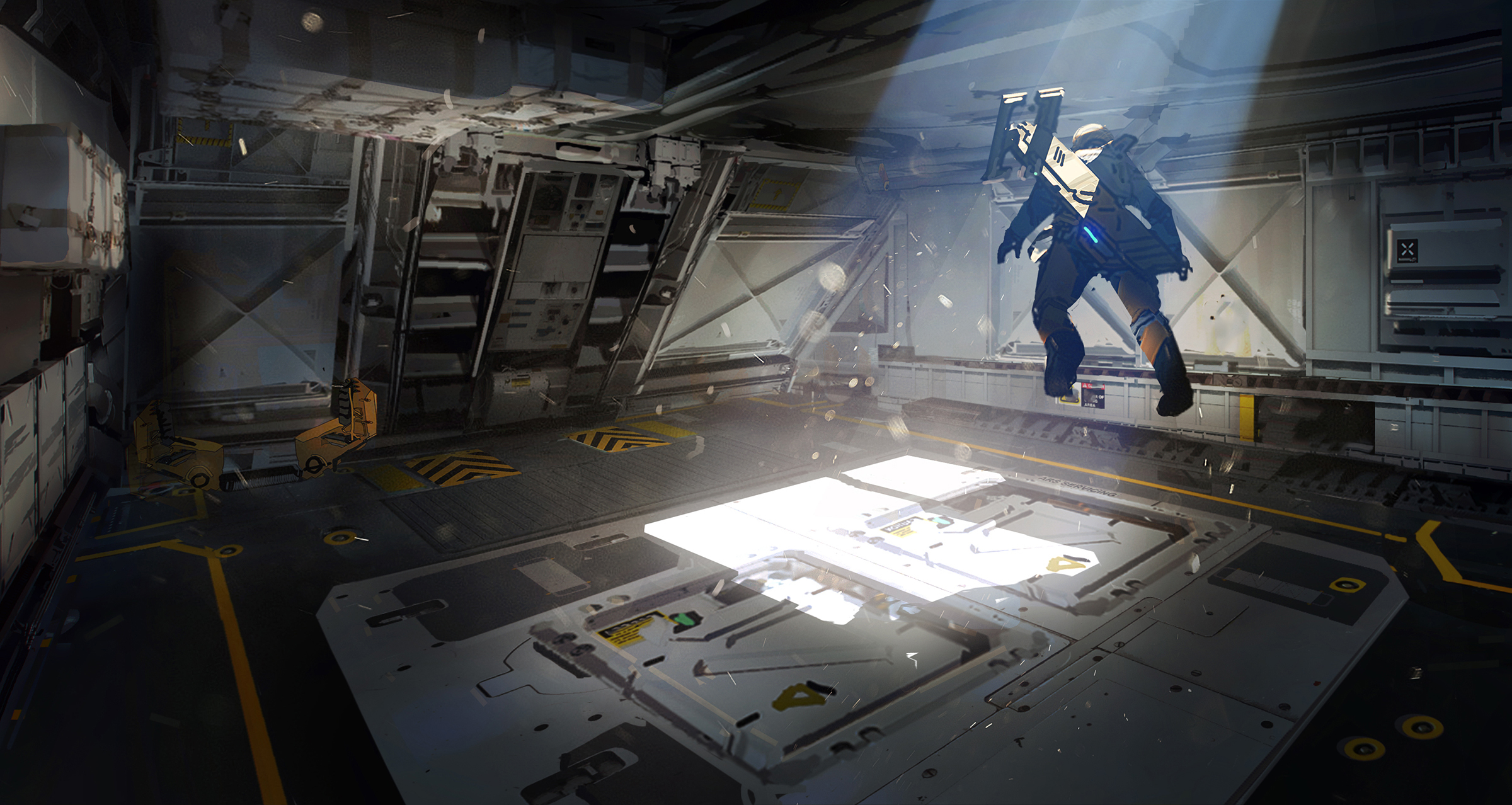

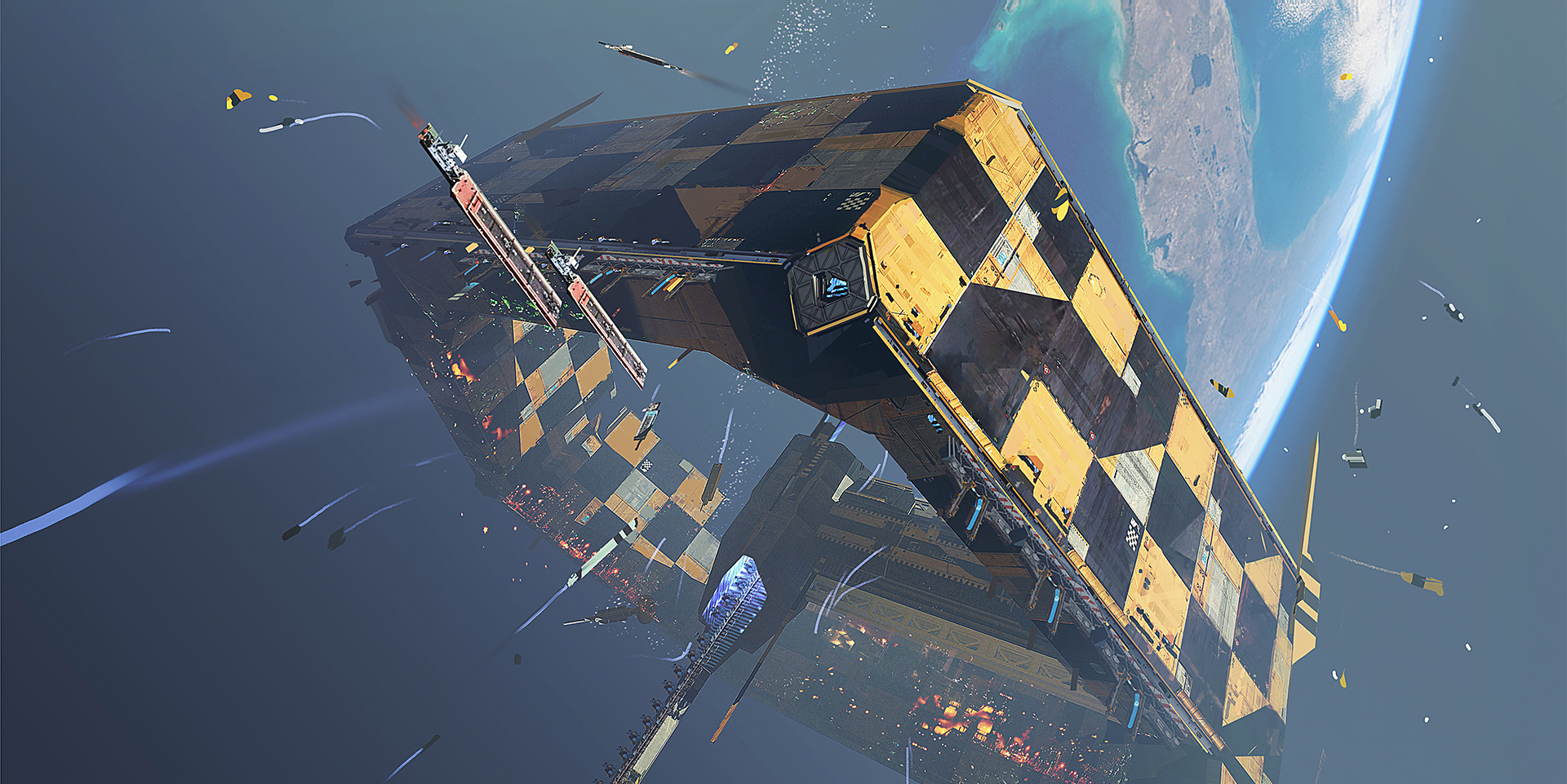

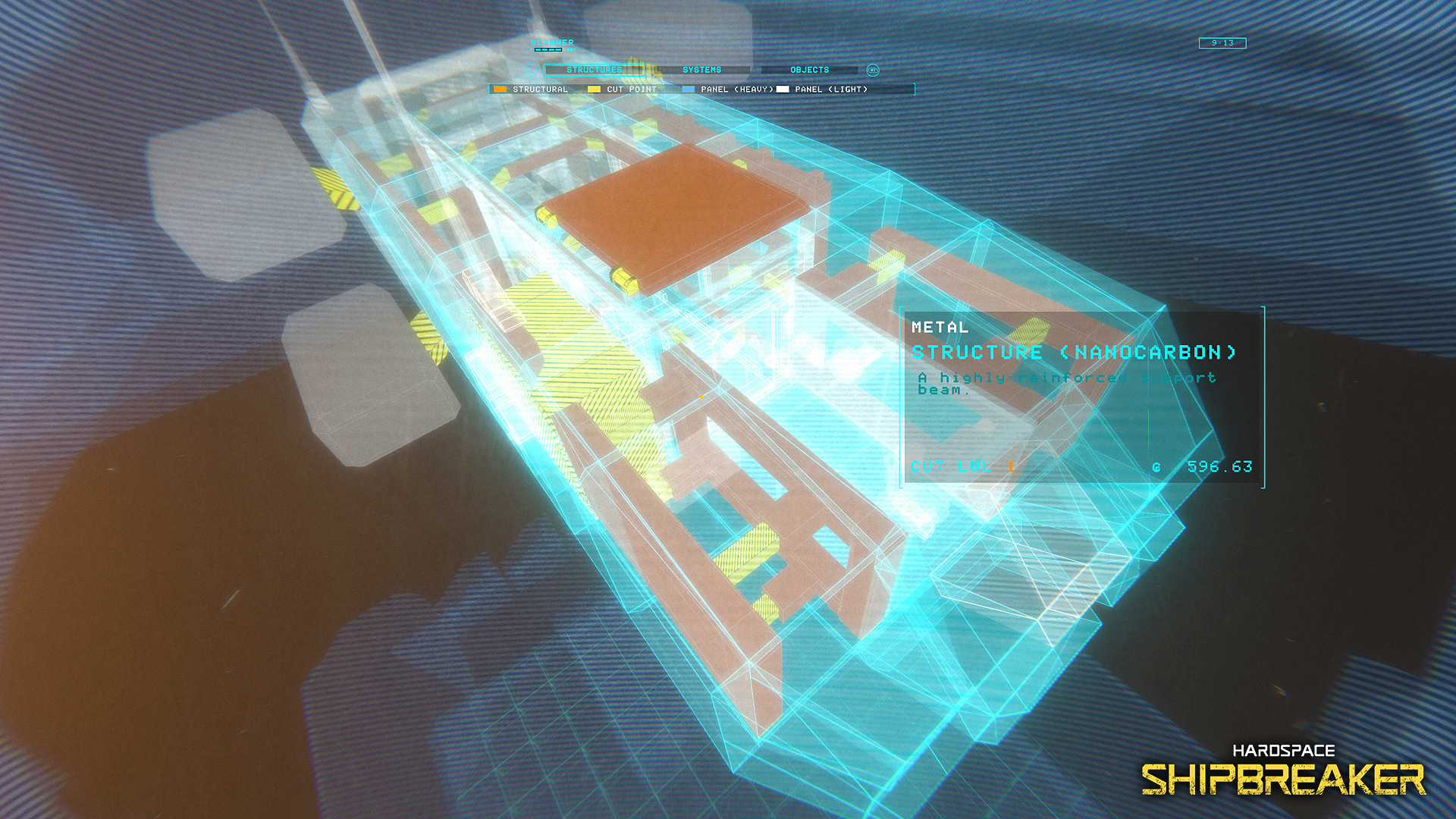

The set-up is simple enough – you’re a menial worker working off a colossal debt in a relatable (if far-off) future, tasked with pulling apart salvaged spaceships. Each ship is procedurally generated to offer you new challenges each time you start a new job. You’ll use cutters, kinetic pulses, and energy tethers to separate aluminum from polycarbon, thrusters from reactors, and useful computer terminals from useless decorations – and blast them into furnaces, collection barges, and material processors. In doing so, you try to avoid death by misadventure… but inevitably fail because of how many dangers you need to face in this job. Every time you die, a new clone is born, even more in debt than before.

It could be repetitive, but a wonderful difficulty curve, the pleasure and pain of navigating Zero-G environments, hefty upgrade trees, and an increasing number of components (and solutions to pulling them apart) turns this into a game like nothing else out there. Add onto that a quietly beautiful storyline satirizing contemporary corporate culture, and lore underpinning a whole new sci-fi universe, and it becomes truly, night-eatingly irresistible.

Like all truly great games, once I was done playing it, I wanted to talk about it. I went straight to game director Elliot Hudson to do just that, and got the story of how this bizarre, brilliant game came together – appropriately enough, from salvaged parts of myriad influences. From its humble origins as a game jam game, its multiple evolutions, its reflections of real life shipbreaking (a profession I didn’t even know existed until the credits rolled), and how it may well be the start of an entirely new series, this is the story of Hardspace: Shipbreaker.

“I think for us, Game Pass was just a no brainer. We had something we knew some people like, and any opportunity to lower the barrier of entry and get in front of more people, we were going to do that.”

The Game Jam

The best ideas tend to come from unexpected places: Shipbreaker is no exception. In 2016, after shipping Homeworld: Deserts of Kharak, Blackbird Interactive had a gap to fill between major projects. To fill that gap, the studio organized a game jam – but it wasn’t just for its traditional developers: “It was like a one-week game jam, split into five teams, I think. Literally everyone, even the accountants and IT people, were involved, it was pretty fun. And there were a bunch of really cool ideas that came out of that.”

“One of the projects that I worked on for that game jam was a game called Hello, Collector,” says Hudson, “where you played this person working for a huge company, and she would just get sent alone out to the deepest, darkest parts of space to salvage this very precious resource from shipwrecks.”

It’s remarkable how fully-formed Hello, Collector sounds for a one-week project. Hudson says that initial demo included everything from corporate satire (the game would tell you your family would be billed for equipment loss after death – this became a full mechanic in Shipbreaker), to low-gravity movement and physics, and even tiny details like your playable character humming as they work, or breathing heavily as they spin out in zero-G. All of this would make it to the final version.

“It was just something that Blackbird really resonated with,” Hudson adds. “It was a very cool sci-fi experience and something that we thought we would want to explore more – and so that became a full project. It became a sort of cosmic horror game for a while, which is pretty wild. And then, eventually, we started to shift it towards more of a simulation of this workplace and a salvage yard. And it became much more about cutting ships open as opposed to just finding them for scavenging.”

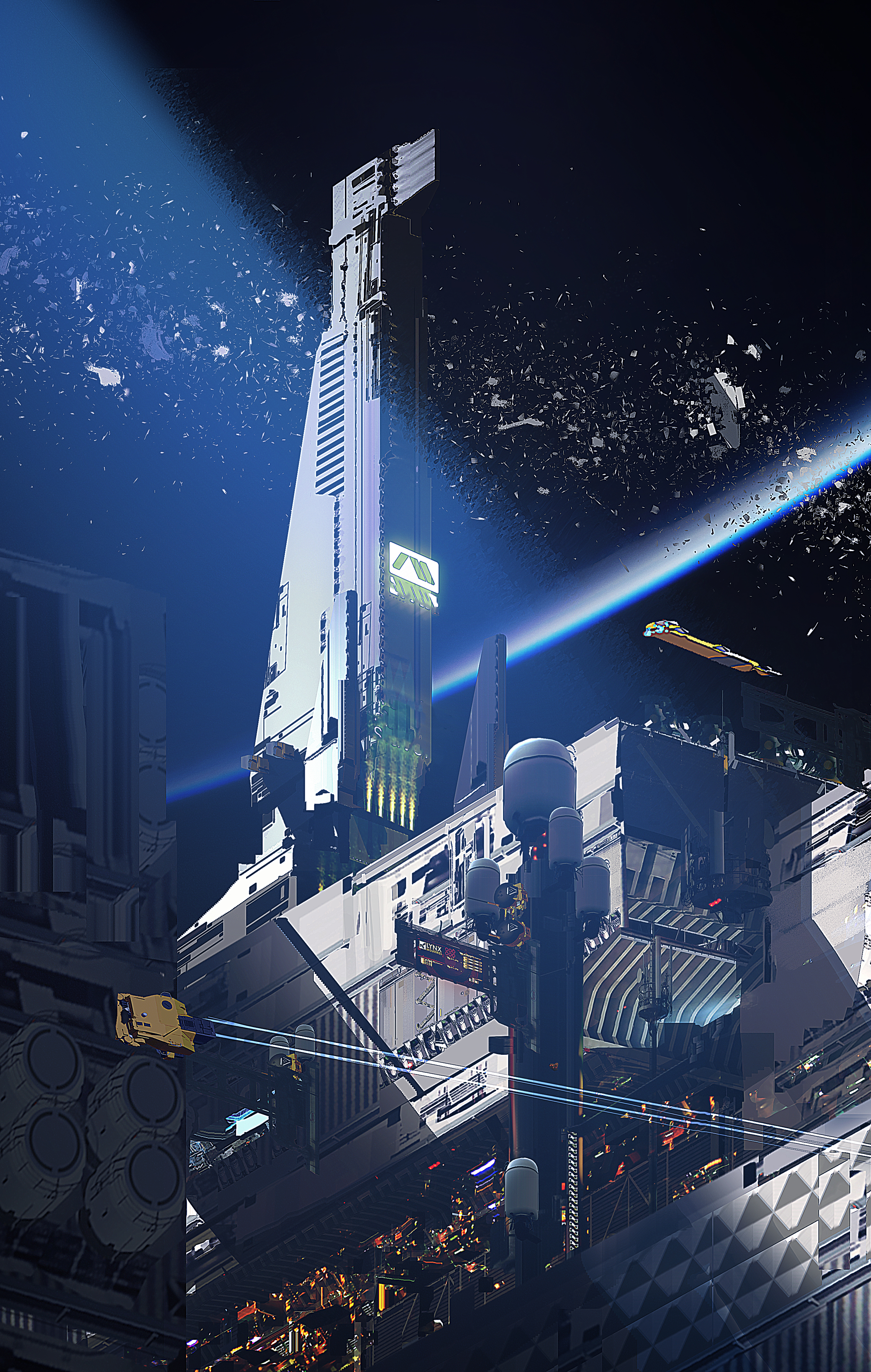

Perhaps part of the reason that Shipbreaker became such an unusual, even unclassifiable game, is that its primary inspiration wasn’t other video games. Shipbreaking is a real-life profession, and Hudson was drawn to replicate it in video game form based in part on a documentary, ‘Shipbreakers’ (which you can watch in full on YouTube). Showing the life of an entire Indian community built on salvaging, it depicts the nobility of work, economic injustice, and the incredibly dangerous lengths real-life shipbreakers go to in order to pull salvaged hulks apart.

Hudson subsequently found further narrative inspiration in the stories of iron workers who helped build modern Manhattan in the ‘20s – “those folks showing up day to day and then climbing these crazy skyscrapers that are super dangerous”. If these don’t sound like your regular video game jumping-off points, that was very much by design.

“I’ll often look to many non-gaming sources for inspiration,” says Hudson, “especially real-world scenarios or historical scenarios. It’s that kind of stuff where I get the most fun ideas from, and I think that that’s really important. I think you see that all over the place in the indie scene, like the games that happen there. Like Unpacking, for example, – who would think that a game about unpacking stuff in a new in a new home would be as compelling as that was, right?”

But the thing about using unique reference points to make a game, and not just tell a story in a game, is that it can become hard to tell people what kind of game it is, and get them to play it in the first place. It’s something Blackbird grappled with from the very start.

“Publishers can be like, ‘Give us the short version of your game,’ and we’re like, ‘Actually, do you have 15 or 20 minutes?’”

Hard to Nail Down

“There’s just a lot about Hardspace that’s very unique – and unusual,” Hudson says. “The way it’s calm, but also highly dangerous, has that Zen quality, but then things can go crazy at any moment.”

Hudson says the freeform, player-led approach was inspired by immersive sims like Deus Ex or Dishonored. But you just wouldn’t call Hardspace: Shipbreaker an immersive sim. Equally, it has some of the qualities of traditional simulator games – but it’s not truly simulating anything we know of. It’s a 3D puzzle game of sorts, but it doesn’t follow traditional puzzle game rules.

“We could tell that we were doing something really unique because we really had a hard time just finding stuff that compared to it,” Hudson explains. “It’s hard, and kind of scary. You don’t know if this thing’s going to play with folks or not. And it can be hard when you’re doing things like talking to publishers and stuff. They can be like, ‘Give us the short version of your game,’ and we’re like, ‘Actually, do you have 15 or 20 minutes?’”

The answer, in those early stages, was Early Access. It was a great move: “The success in Early Access right out of the gate showed us, ‘Okay, we’re onto something.’” Hudson makes clear that Shipbreaker would always have reached a final version, but Early Access actively changed what that final version would be, even influencing some of its most memorable features. Players reacted well to the game’s nuggets of story, contained in data drives floating through ships – Blackbird felt emboldened to double down on its campaign narrative, fleshing it out to tell a story of a group of workers (all inspired by real people Hudson and his team have worked with in the past) unionizing and fighting against the indentured servitude they’ve unwittingly entered.

Two of the game’s most memorable features even emerged directly out of player feedback (and we’re entering some spoiler territory here, beware). One of the game’s later mechanics sees you beginning to work on ghost ships. Their origins redacted and their crews missing, ghost ships turn the experience into a soft horror game: doors open and close on their own, systems whir to life without you touching them, airlocks can eject you seemingly of their own volition, and it becomes clear that each one is haunted by a malevolent AI. All of this came from an unexpected source – a single data drive entry.

“It was a very mysterious entry from the voice of the Machine God, talking about wanting to take over the living world. It was kind of a one-off thing that we had in there just to sort of broaden the world of Hardspace in a bunch of ways. But players would talk a lot about it. I sort of hit on this idea of taking the Machine God that people are clearly interested in, expanding on that a little bit and actually incorporating it into gameplay and having the ships be like haunted houses that are that are run by this Machine God.”

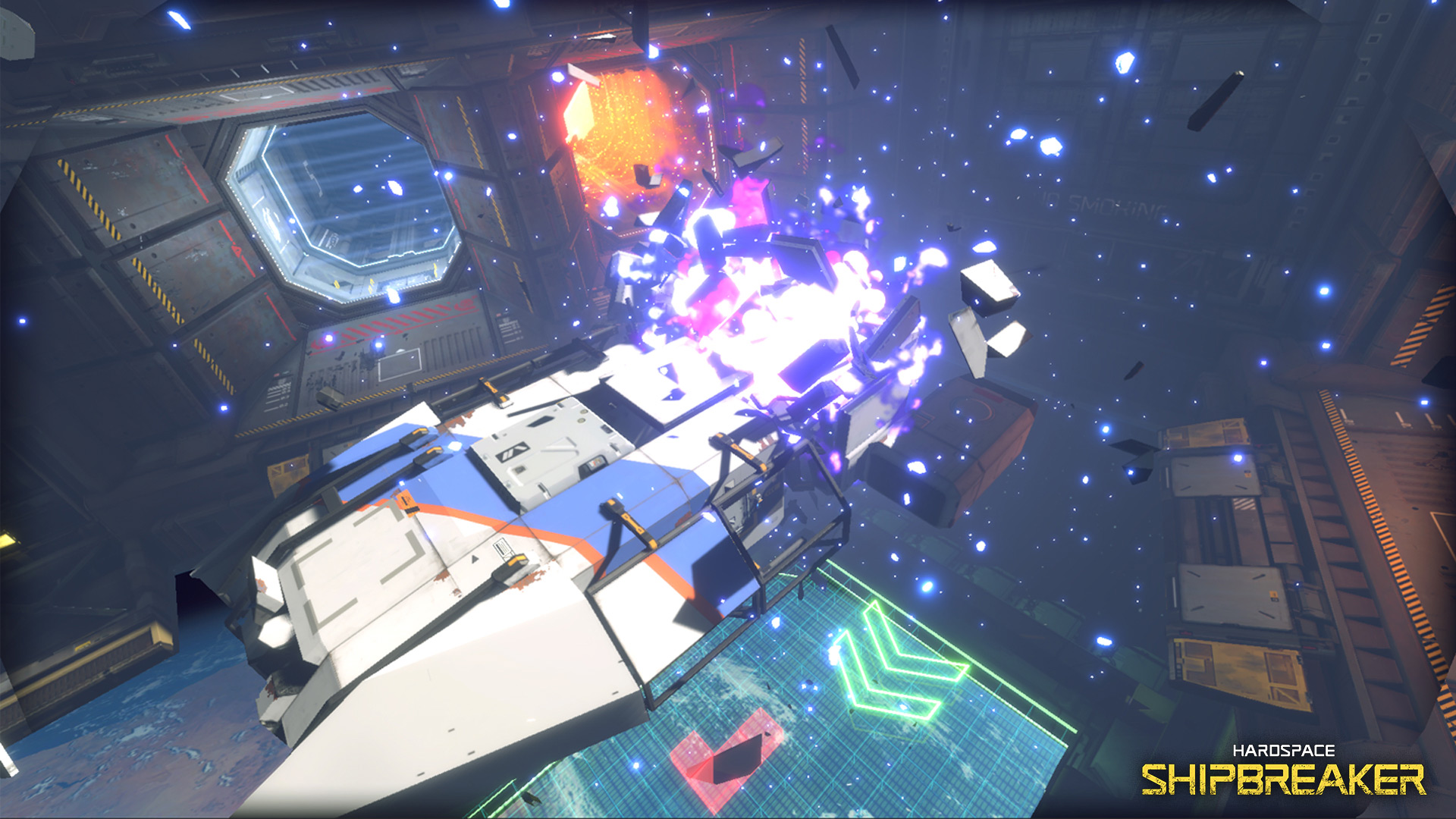

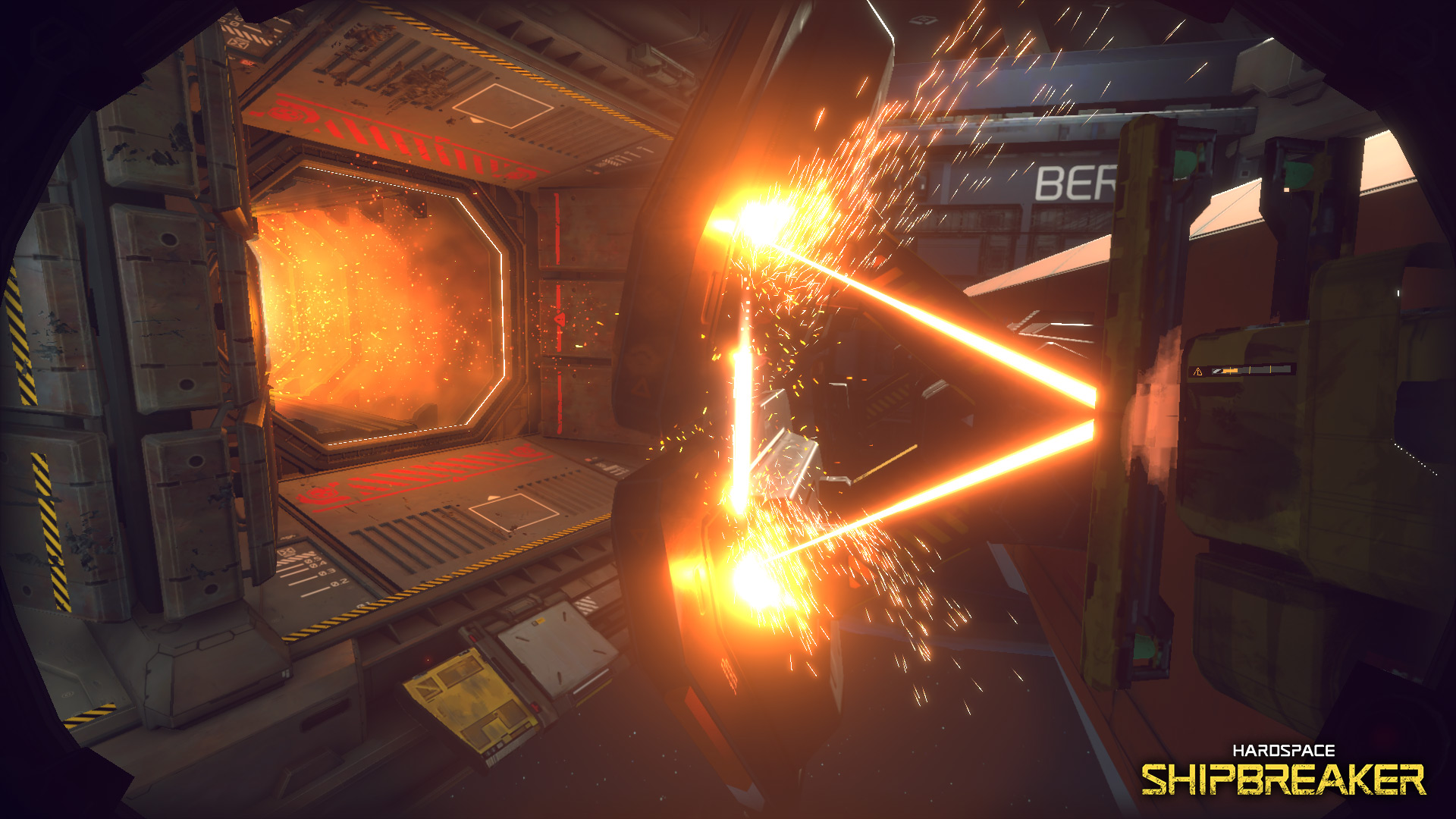

But players would help spawn an even more important facet of the game – its action climax. Industrial Action is a unique mission at the end of the game’s storyline in which the game’s characters don’t just go on strike – they begin wantonly destroying the ships you’ve spent so many hours carefully piecing apart.

“Almost from the get-go in Early Access, folks would say, ‘Hey, you guys need a Demolition Mode. I want a mode where I can just go in and smash the crap out of this thing, like we’re playing Burnout, or we’re beating up the car in Street Fighter. And then when we were talking about the story, and wanting to come up with an interesting way to have the gameplay change meaningfully in the final act of the game, that’s where we were like, ‘Oh, just bringing destruction back in at that point is a really interesting inversion of everything that the game is up until that point.’”

Hudson is happy with how varied the feedback is on the moment – some players love that it’s a single event, others want more, and some players were even upset that they had to do it after spending so long mastering their shipbreaking craft. “There were very interesting reactions to that moment, which is why I think it was so successful,” says Hudson.

That willingness to work with the fans, to craft a game in concert with its audience, is another facet of Shipbreaker’s brilliant approach to taking inspiration from less obvious places. It became the game it is by inviting people into this unusual experience, and asking what they’d like to see more or less of. That inherent openness is also what led it to Game Pass, and greater success.

“It’s almost more important just to get people playing this game and invested in this world that we’ve built… and then we’ll see what we do in the future.”

Game Pass – and Beyond

“I think for us, Game Pass was just a no brainer,” Hudson says. “We had something we knew some people like, and any opportunity to lower the barrier of entry and get in front of more people, we were going to do that.” Hudson explains that Game Pass is invaluable for games like Shipbreaker because it encourages players to experiment with games they might not have considered otherwise. Since joining the service Blackbird has seen the numbers of new players entering the game become more consistent – people are intrigued, and can hop in to see what this unusual game is all about almost immediately. “It’s almost more important just to get people playing this game and invested in this world that we’ve built,” says Hudson, before teasing fans a little by saying, “And then we’ll see what we do in the future.”

As you might be able to tell, Hudson and Blackbird’s plans for Hardspace do not end here. While Shipbreaker itself has reached a final state (as much as I might clamor for a crossover DLC where I get to disassemble Mass Effect’s Normandy, it seemingly won’t be happening), its commitment to building a whole universe in the margins of a seemingly small-scale story, and its success in reaching players through Early Access and Game Pass means that the team is investigating how to make new games in this world. That ‘Hardspace’ title prefix shows how confident the team is in its vision for a new gaming series.

“I often find that when I see other games come out, and it’s the first one in the series but they have that prefix, I’m always like, ‘Come on, man. Really? Are you really gonna do a full thing?’ I’m always kind of judgmental of it,” Hudson laughs. “But then here we were working on Shipbreaker, and just the amount of ideas for it… now we’re one of those people with a prefix with only one game.”

The beauty of Hardspace’s vision – a world inspired not by other games, but echoing real-world concerns and historical moments – means that this isn’t a case of just getting a Shipbreaker 2. Hudson makes clear that future Hardspace games would aim to investigate different things, meaning different kinds of mechanical experiments to go with them:

“The whole point is we really wanted Hardspace to be a world that we can do other things in. Shipbreaking is definitely the part that we wanted to explore first, but the idea is that there’s lots of other room in this universe that has pretty interesting things to talk about. So the whole point was to create something that we could expand on in the future.”

What those ideas are, Hudson won’t tell me. And, honestly? I’m fine with that. The pleasure of Shipbreaker is that everything that led to making it what it is – those unexpected inspirations, its game jam creation, its following of the fans – led to something that can feel rare: a true surprise. I’m ready to be surprised again.

Hardspace: Shipbreaker is available now on Xbox Series X and S consoles and PC, with Xbox Game Pass and PC Game Pass, and Cloud Gaming.

Hardspace: Shipbreaker

Focus Entertainment

Hardspace: Shipbreaker (PC Version)

Focus Entertainment