I think the biggest compliment I can give to the music of Starfield is that, as I write the game’s title, the theme tune always plays in my head. More specifically, the motif – duh-dah, duh-daah, duh-duuuuh – if you’ve played it, or even watched a trailer, you know the one. Those six notes are woven around the very bones of the game, from its title screen to its level-up alerts and, after tens of hours, begin to feel more like its beating, hopeful heart than mere sonic set dressing.

As it turns out, in an alternate timeline, we may never have heard them. “Today, we can admit that, in the first two years – two years! – of the development, we actually had a different theme.”

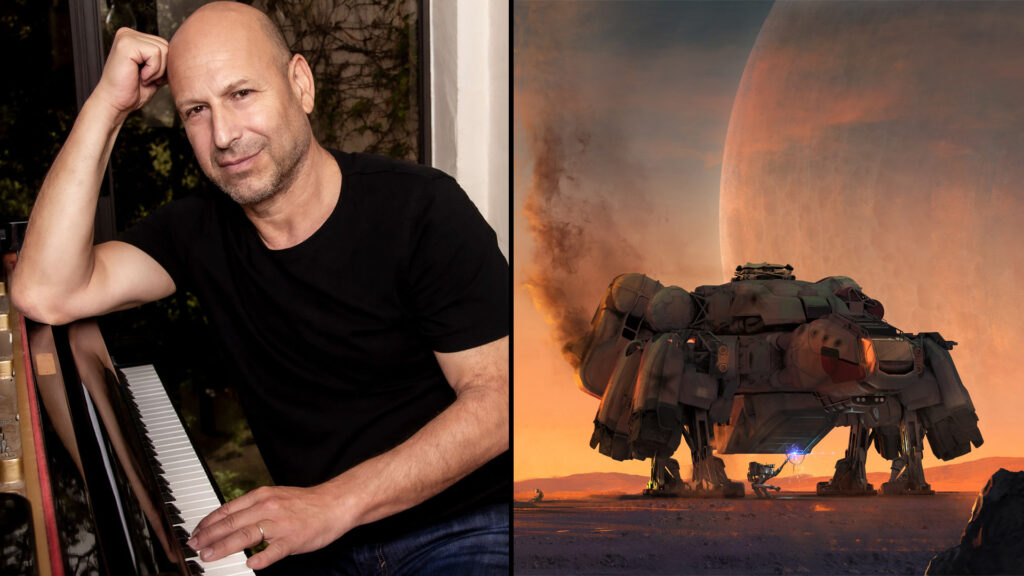

Composer Inon Zur – the award-winning architect of Starfield’s score, long-time Bethesda collaborator, and composer of over a hundred soundtracks across gaming, film, and TV – drops this reveal early on. I’d mistakenly assumed that those six notes formed the start of all his work on the game, but the reality was more complex – and speak to how seriously he and Bethesda Game Studios take the job of finding a musical identity for their games.

“Todd Howard pretty much signed off on [the original theme]. He liked it – and then two years later, Todd said, ‘You know, I’m listening to it again and again and again, and I like it, but I don’t love it.’ That was pretty much the end of that theme. So I just started a new theme, and this is what you hear now.”

There’s no hint of regret in the way Zur talks about that shift – in fact he seems energized by it. After years of working with Bethesda, Zur knows that finding the exact right tone is key for both him and the studio:

“We believe that every game needs to have its own DNA. This is a philosophy that Todd Howard is always focusing on; it’s so important for him to really hammer the DNA of the game. So it’s the appearance, it’s the story, and it is the music.

“So, what we called that musical signature, when you hear it, [we want you to] know it’s Starfield. Like, Star Wars: [sings the Star Wars refrain] – you hear it, you know it’s Star Wars. And I think Bethesda really did this very, very well in the way they incorporated the music inside the game. So there is no mistake that this is the signature of Starfield.”

So, in creating that musical signature, where did Zur and Bethesda land on the DNA of Starfield? What sparked his creative imagination?

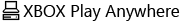

“So there are three elements that came to mind right away when I thought about Starfield. Imagine that you are being thrown into space. So first, you have this ‘awe’ feeling: it’s so big, it’s so vast, it’s incomprehensible. Then comes the fear: the fear of the unknown, the fear of everything that could happen in this whole new place. And then with it comes the excitement: the opportunity to discover new worlds, and to experience something that people have never really experienced before.

“So take these three elements – the awe, the fear, the excitement – and listen to the music of Starfield, and I think you could get that. There’s always the mystery, there’s always the insecurity, the feeling of, ‘we are not safe, we are in an uncharted territory’, but then there’s always the excitement and positive attitude: ‘Yes, but we will go, we will experience it, and there are new opportunities out there.’”

That idea of positivity in the music of a sci-fi game feels like the biggest outlier to me – science fiction so often puts fear or conflict into the forefront of your experience, but Zur’s score resists solely taking that path. There’s a hopefulness to his work here that reflects the game’s own outlook.

In part, that’s down to how he used instrumentation – sci-fi, as you’d expect, lends itself well to electronic music, but much of Starfield’s backing feels more classical in tone, harking back to the likes of Star Trek’s themes, and their own, more joyful takes on the future. Zur’s challenge here was in combining the two sides – classical and electronic – to create something that feels like a new whole.

“I think that the more classical tone is the more dominant one in our [score]. However, if you listen to the whole score, there are many areas where electronic and sound design elements are 50, sometimes 60, or even 70% of the score. The score is vast and there are many cues that are actually not what we call classical at all. I think the interesting thing is the combination that we created.

“At many points, you cannot really put your finger on what is sound design, what is electronic, and what is orchestral, because everything really is intertwined. Sometimes there is a more traditional accompaniment, or orchestral background, but then the instrument that carries the melodies is actually synth. And sometimes it’s the other way around; there’s more ‘sound design-ish’ elements, but the [main] instrument is classical.”

The result is a score that can slide from mood to mood, style to style, seamlessly – helped by the fact that it’s enormous, surpassing the five-hour mark. Of course, five hours of music is still a fair bit less than the hundreds of hours some players will put into a game like Starfield, meaning Zur’s other challenge was in crafting a score that can keep hitting its key themes without feeling overly repetitive.

“It’s about finding this balance between, ‘How can I create something new, but make it feel like part of the same family?’ There are many ways to go about it: you could change the timbre, you could change the tempo, you could create variations that are different enough, but still remind the player, ‘Oh, yeah, this reminds me of the theme’, but it’s not the theme, it’s something different.

“It’s like painting. If you add a little bit more grey or black, automatically, the painting feels more gloomy. And there’s a way to do it in music. It’s almost like drawing the picture and fine-tuning the colours and themes. In this way, you create environments that are different enough, on one hand, but then still part of the same DNA.”

Which leads us back to those core six notes – notes I must have heard hundreds of times in my time with Starfield, but played over so many different moments, and earned a different meaning by doing so. I tell Zur that when I think about those notes, I think of Starfield, and when I think about Starfield, I think about those notes. Was that the intention?

“That’s actually the best thing a composer can hear. It’s not only about the composition, it’s also about how it’s being implemented. But really, if a composer hears that, that means that he or she did a good job… I think that a lot of props need to be given to Bethesda, to the Audio Director, Mark Lambert, and Todd Howard, who oversaw everything. They made sure that the music really feels like it is growing out of the game.”

“This is so important, because there are very few movies or games that do that. Like Halo, for example: you think about the game and you hear the music. And I think that Bethesda’s games really do this well too. Music is such an important part – when you think about The Elder Scrolls or Fallout, you automatically hear the themes. It’s also part of the way Bethesda is playing those themes – they’re repeating the theme a lot, and they’re making sure that the theme works so well, inside the game, that it becomes an inseparable part of it.”

Starfield’s music truly is inseparable from the game, powering and being powered by the rest of the game’s many interlocking parts. Zur tells me that, for him, “the perfect music for a game is music that you feel, you don’t hear” – it’s hard to visualize, until I think of that motif, those six short notes. I heard them at first, but I feel them now.

Starfield

Bethesda Softworks