Martha Is Dead Is out Now on Xbox Series X|S

Summary

- First person psychological thriller set in 1944 Italy, blurs the lines between reality, superstition and the tragedy of war.

- Explore the game’s immersive Tuscan setting, take photos using the 1940s era camera to help uncover the mystery of what happened to Martha.

- Discover how the development team created the rigging and made the photography equipment behave realistically.

Hi!

I am Lorenzo Conticelli, Lead Environment Artist and Lead Animator at LKA, working on Martha Is Dead.

The journey to release has been a long one, we’ve been working on the game for the past four years and it is finally available on Xbox One and Xbox Series X|S!

For anyone who is new to the game, Martha Is Dead is a first-person psychological thriller set in Italy in 1944, against the backdrop of World War II. You play as Giulia, investigating the death of her twin sister, in a dark, tense, emotional story that combines real-world locations, historical events, superstition, folklore, and psychological distress.

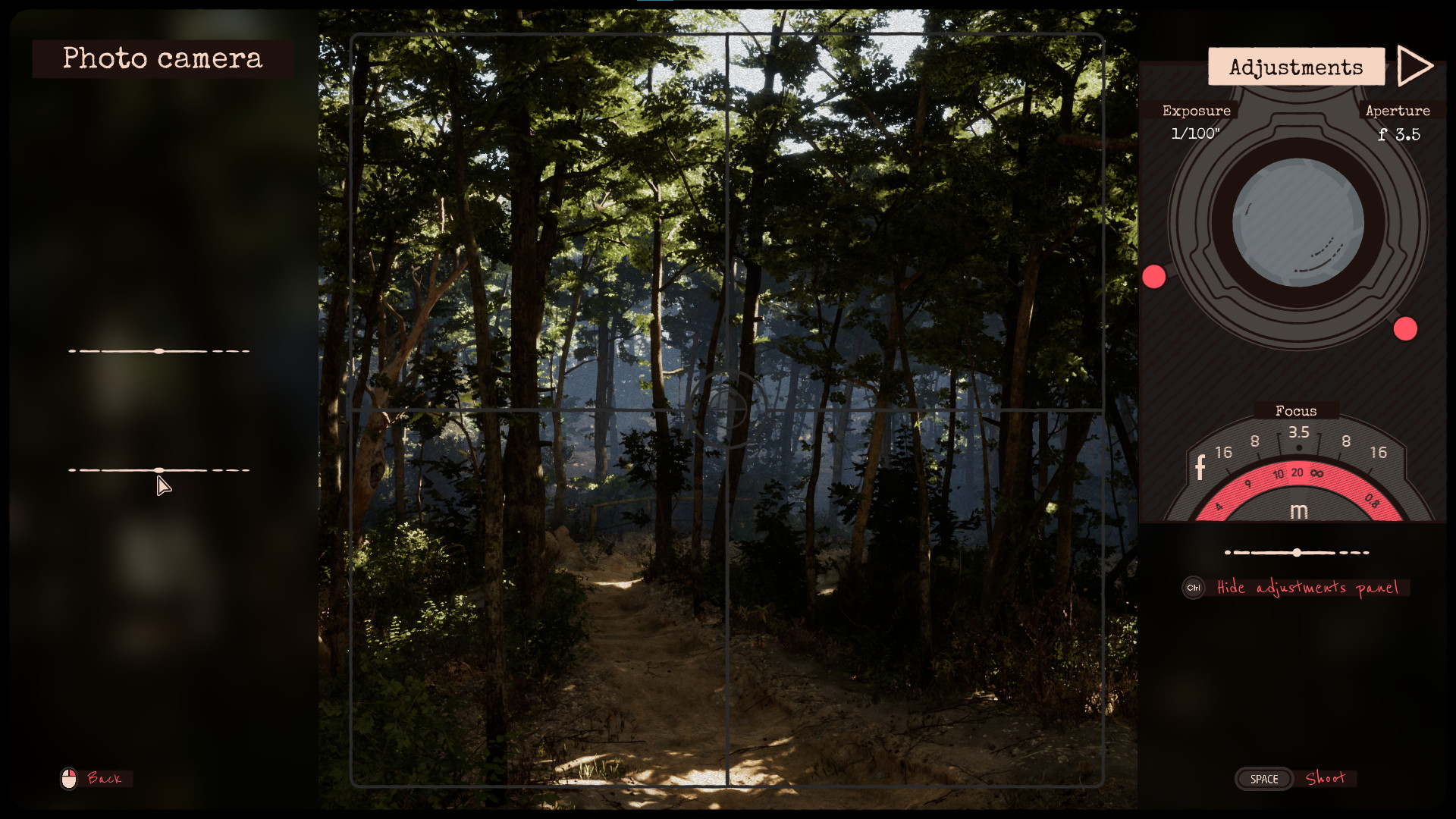

Photography plays an important role in the game and I am here today to talk about one of the coolest things I have worked on! Rigging and making the photography equipment in the game behave realistically and animating Giulia to interact with it.

First, some context. Photography is important in Martha Is Dead because it helps the story unfold, captures missing details, reveals hidden truths and gives the player the creative freedom of taking their time exploring and photographing whatever catches their eye in the game’s beautiful Tuscan setting. You are still in the 1940s though, and photography was different then. Less immediate, but maybe more mysterious and magical, more linked to craftsmanship, where you had to predict the result and master each step, know how light, liquid, paper and films chemically react to each other. And you couldn’t see the result until you had developed and printed the photo you had taken hours (or even days) before. (And yes, the game has a fully functioning darkroom).

So, back to the matter at hand – what does ‘rig’ actually mean?

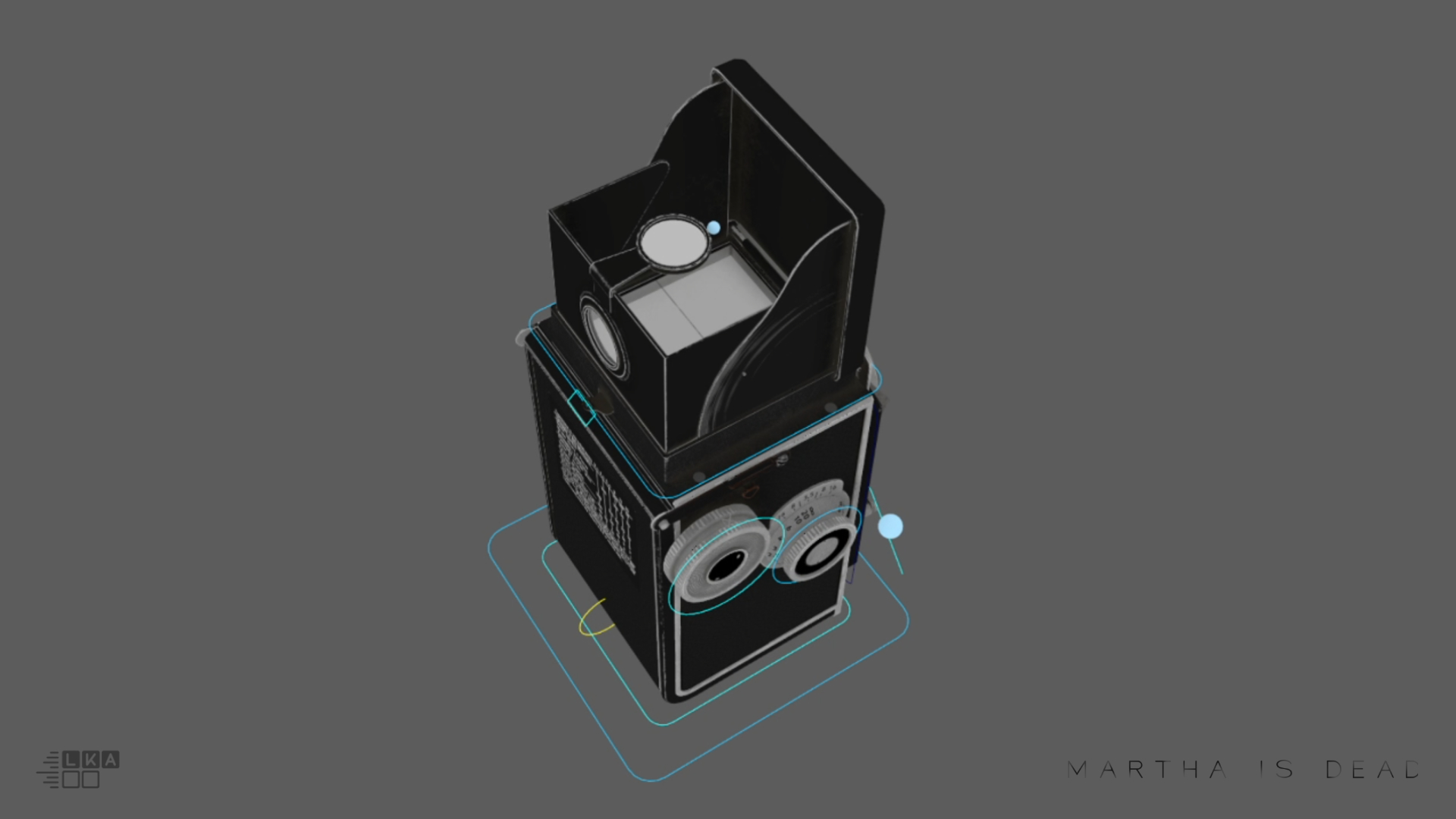

When you have a 3D object modeled and textured, one of the most common ways to animate it is to create bones/joints and controls. Imagine the joints are like human bones: moving one brings the muscles and skin attached to it, like a joint influences the vertices in space. Imagine the controls like a helping hand to manipulate multiple bones at the same time or control particular behaviours. This is valid for all 3D elements, both for organic and hard surface models. So, we need to create bones even for a door or a camera, like our Rolleicord model K3 camera.

In order to recreate it digitally we needed to understand how an old 1940’s camera worked. My background in photography helped me during this study phase, because I already know how the lenses, gears and shutter work. But the most useful thing was that we had a real Rolleicord camera in our office from the 1940’s. So, we could study directly from the model; seeing how one gear controls another, or how a small stick changes the exposure time. It’s really fascinating to me and was of priceless value.

We decided to recreate all of the possible movement allowed for the camera, so even if you don’t see it when Giulia uses it, now you know that the camera works like a real one.

The enlarger was a fun part. I underestimated it at first as it seemed simple, but it was a pretty complex rig. When Giulia pulls down the main light projector, it should remain in the same axis otherwise the projected photo will be displaced from the paper below. This was pretty complex due to the rotation and the use of a spring, but in the end, I was pretty satisfied with the result.

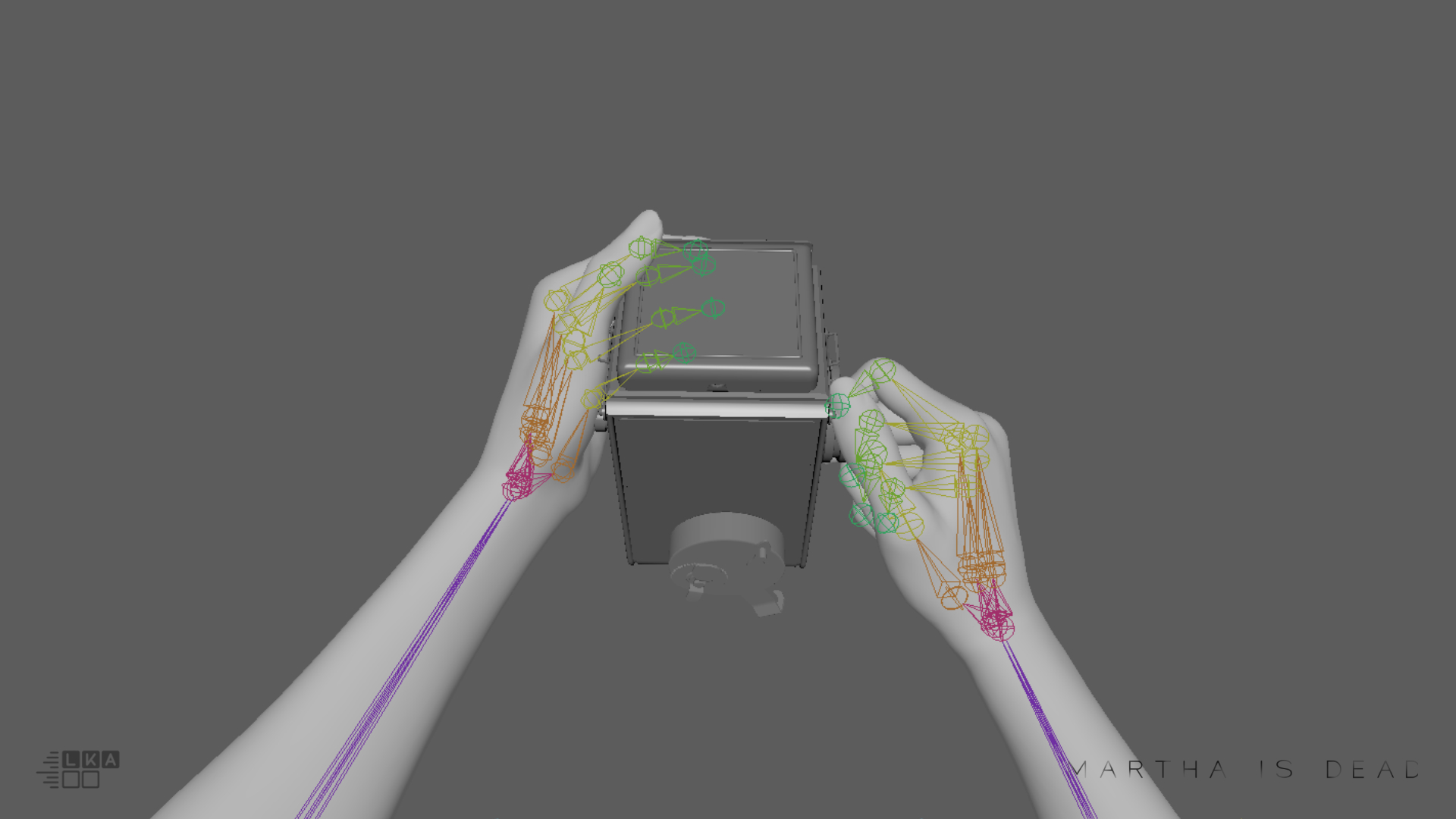

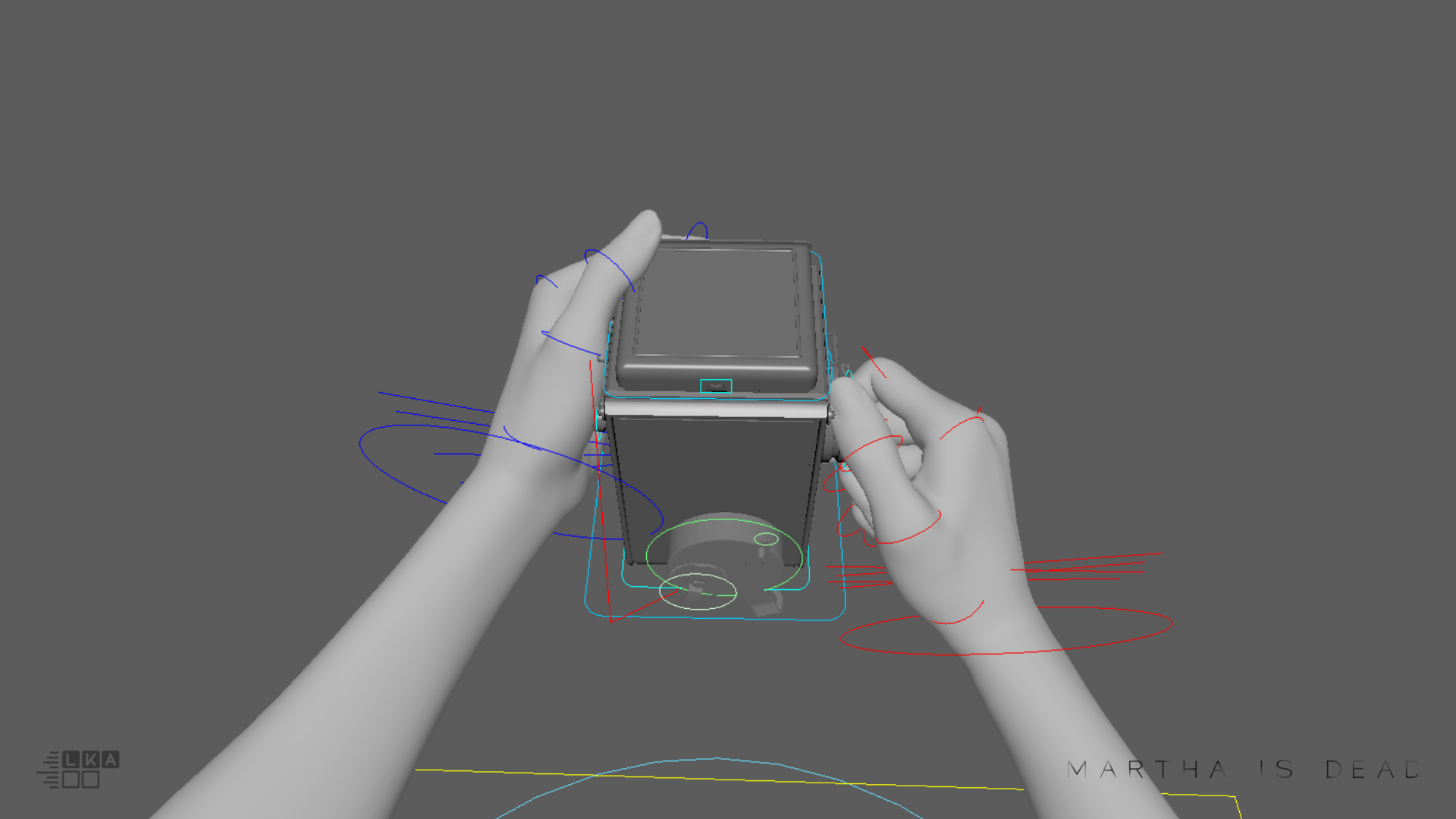

Keeping the camera on my desk also helped me a lot during the animation stage. Feeling it in my hand helped me to give a digital weight when Giulia handles it in game. Seeing how the hand grabs the camera, how the finger moves to reach a gear helped me to recreate the movement as naturally as possible. We decided to not use “mocap” (motion capture: recording a real actor’s movement with sensors on his/her body) for the hands and fingers. The results were pretty noisy and unpredictable when dealing with such small sticks and gears. Cleaning up all of the mocap’s animation curves and trying to keep the fingers steady in place time-consuming than hand keyframing (the traditional approach of saving a pose in a frame of the timeline, then posing the character in a different position, etc.). So basically, all of Giulia’s animations are made from scratch (with a lot of video references).

Check out this slideshow of how the animation of Giulia’s hand in the first scene at the lake works and what is behind it.

Martha Is Dead is out today and I hope you will enjoy using the photography equipment in the game as much as I have enjoyed recreating it!

Martha Is Dead

Wired Productions