Hi-Fi Rush: From a Little Idea to a Very Big Surprise – The Exclusive Oral History

Summary

- The talented development team at Tango Gameworks shares in their own words the story behind one of 2023’s biggest surprises: Hi-Fi Rush.

- From the early stages of development and through release, we get an exclusive peek behind the curtain of game creation on today’s platforms.

- Hi-Fi Rush is available to play today on Xbox Series X|S, Windows PC, and with Xbox Game Pass and PC Game Pass.

Hi-Fi Rush turned us up to 11 before we even knew what hit us.

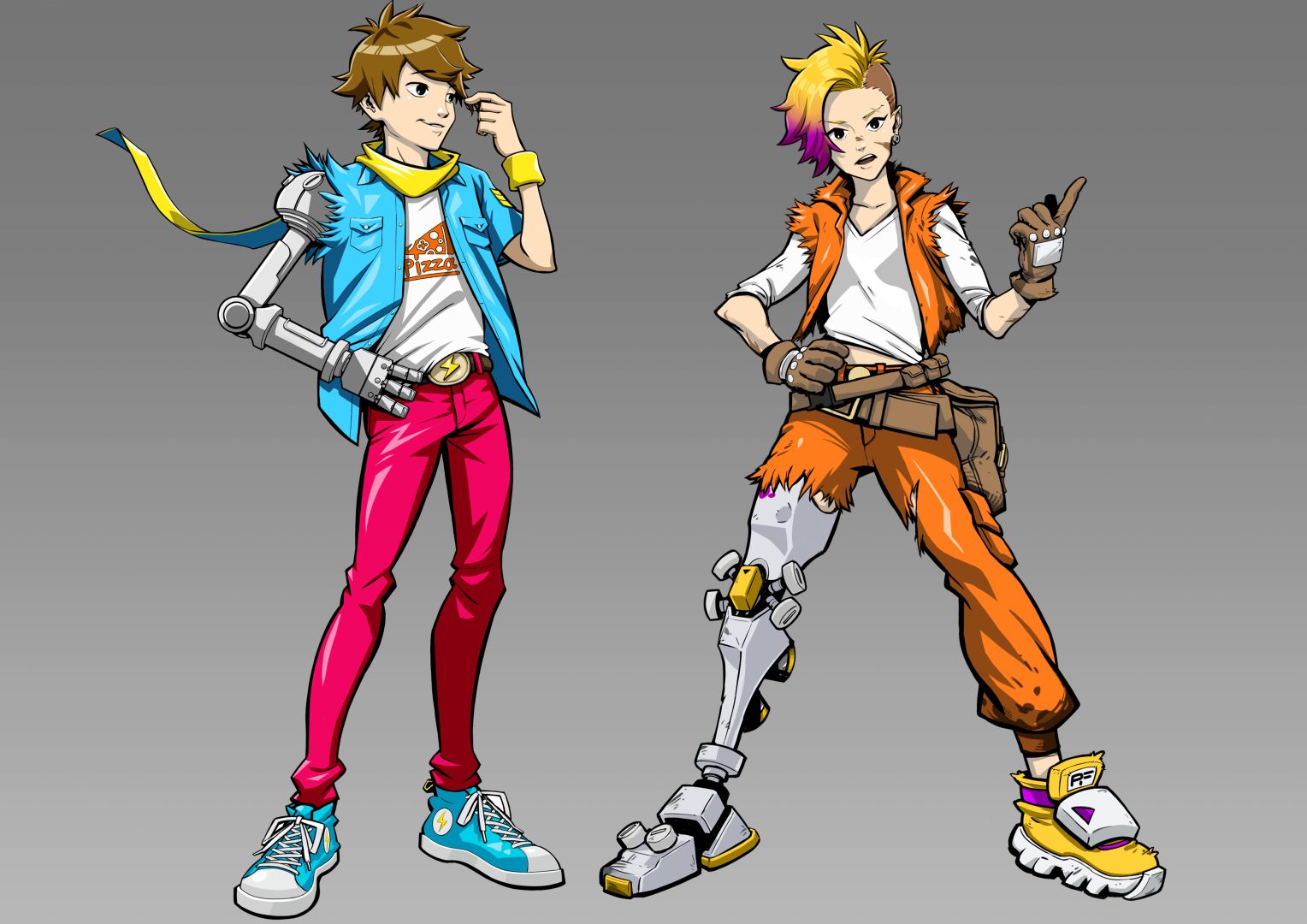

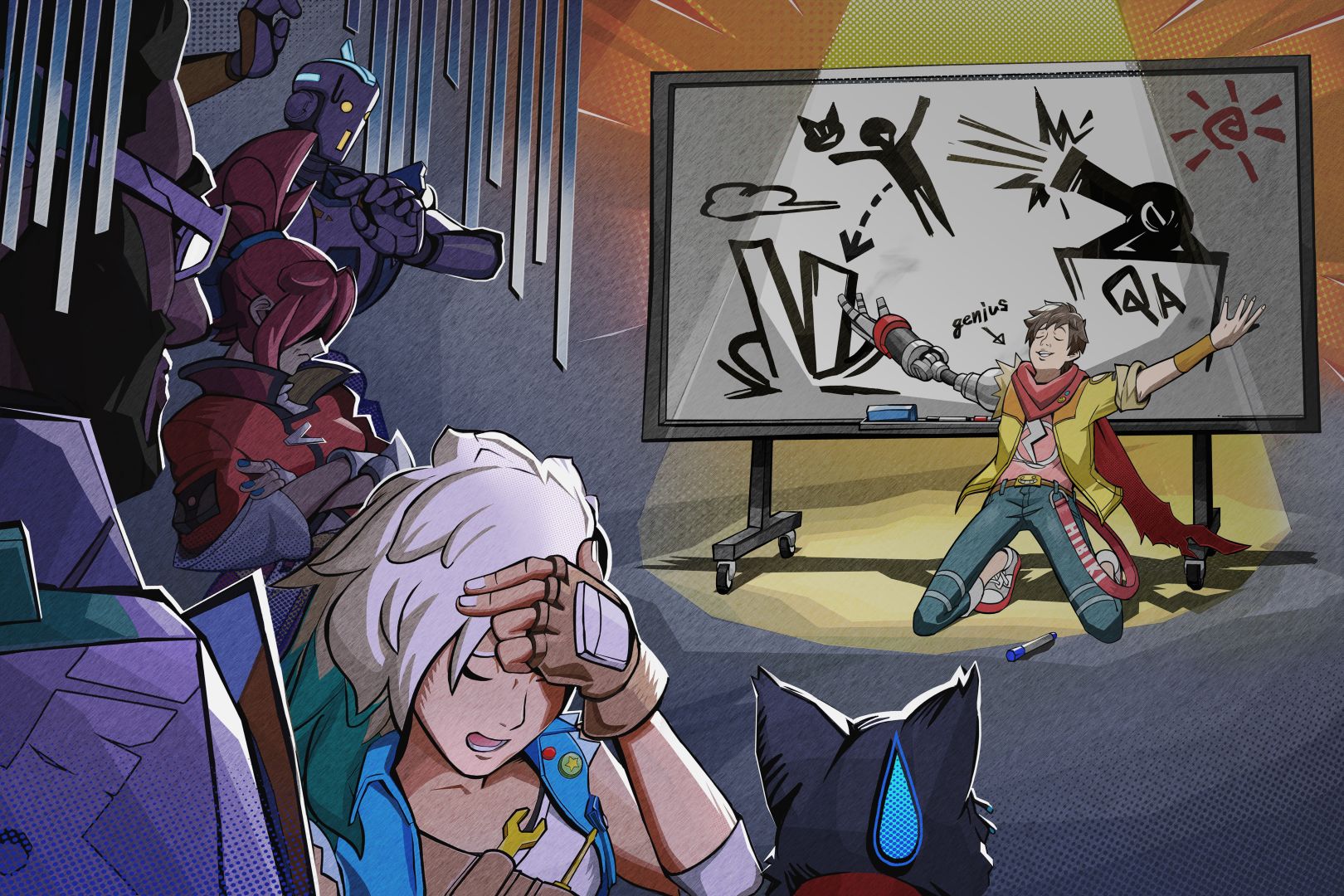

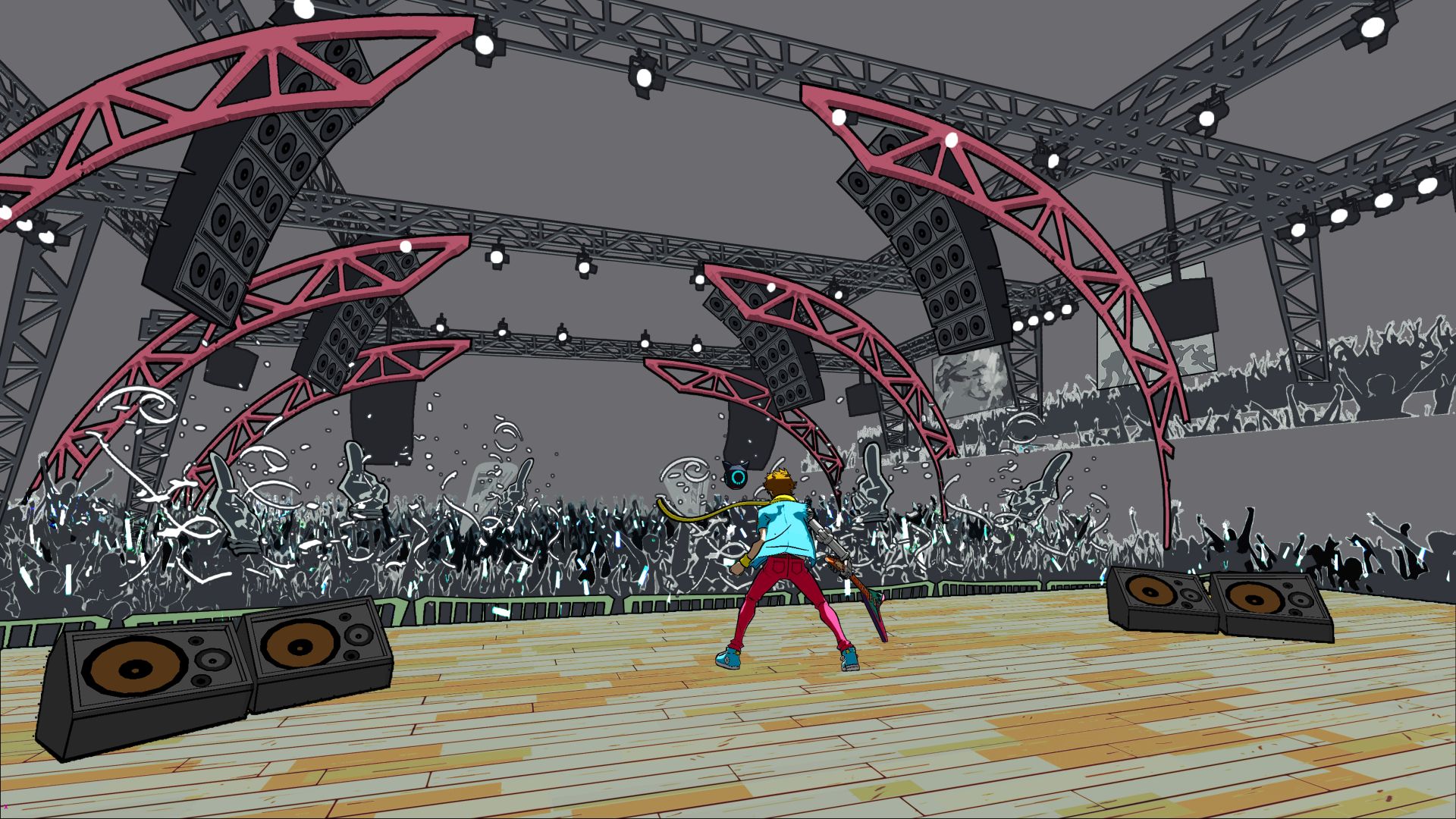

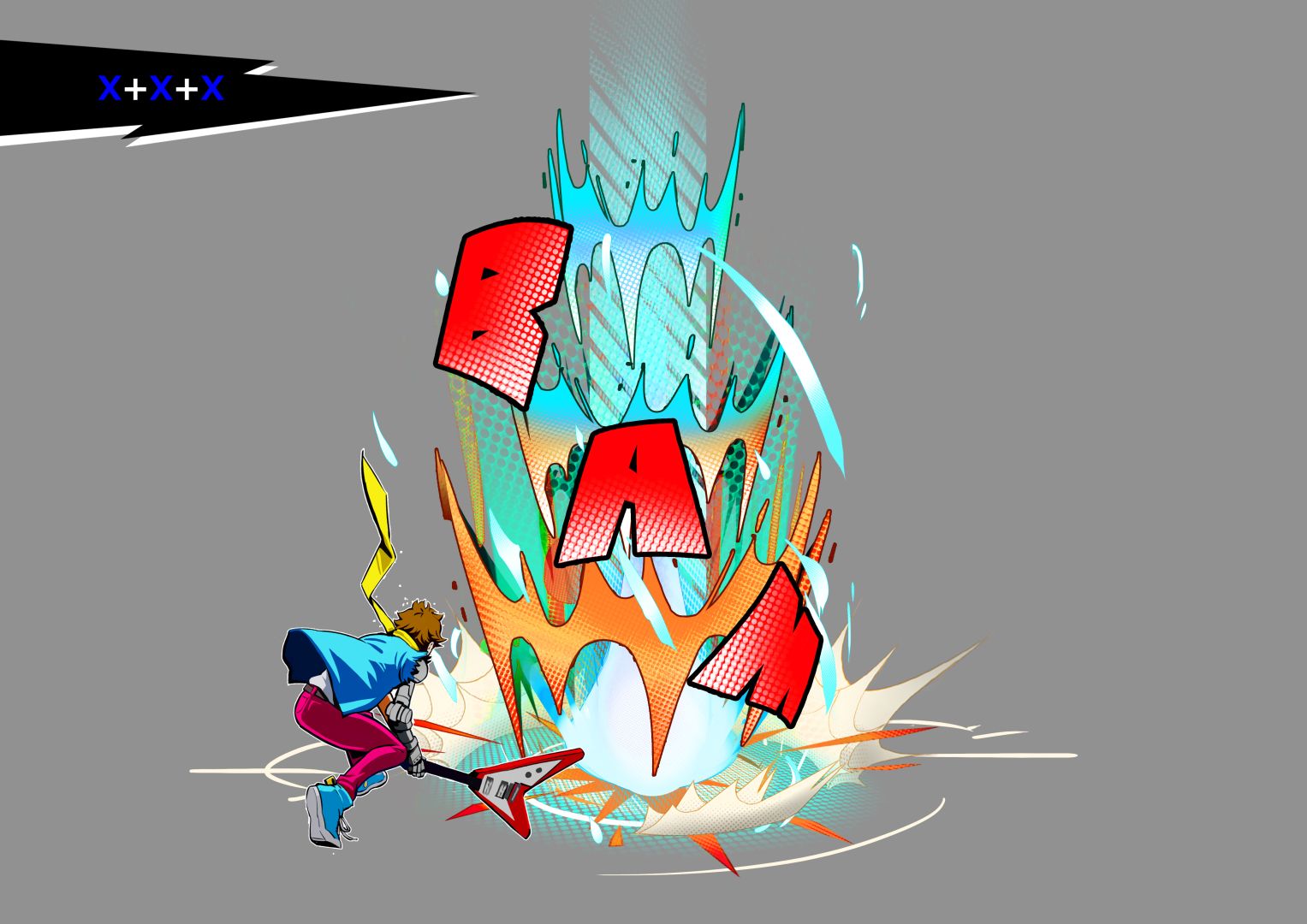

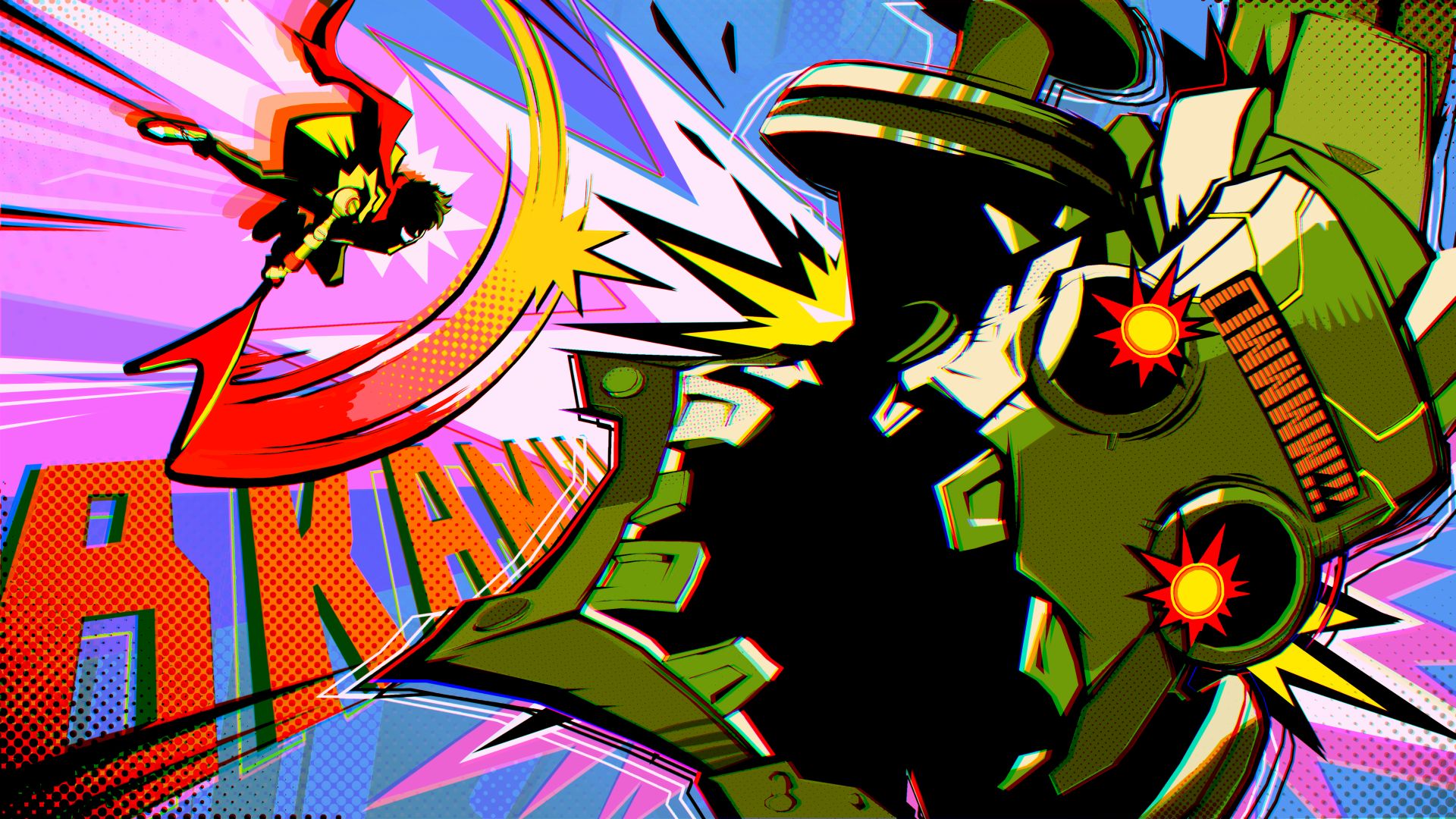

In one of the year’s biggest surprise releases, Tango Gameworks – a studio that cut its teeth on the paranormal genre with excellent projects like Evil Within 1 & 2 and Ghostwire: Tokyo – launched Hi-Fi Rush and served notice that its talented group of game developers were much more than just “a horror game studio.” Hi-Fi Rush was brash, bold, colorful, and most importantly, fun!

This incredible project — which had been developed in secret at Tango for nearly five years — pleasantly knocked its custom-built guitar over our heads with its crisp, rhythm-based gameplay, excellent soundtrack, and memorable characters, all wrapped up in a unique world for us to explore.

Because of its “shadow drop” release, it bucked the trend of a preview circuit (announce, hands-on previews, etc.) so we haven’t had a chance to follow the game’s creation – until now.

Xbox Wire was given exclusive access to talk to the heads of development at Tango Gameworks to bring you this unique, behind-the-scenes look at the inception of an idea as it moves through the entire creative process, right up to its full release.

Throughout this piece you’ll learn how Game Director John Johanas first pitched his dream project to the heads of the studio, how Lead Programmer Yuji Nakamura helped create the initial prototype that would be the framework the team would follow, how the team arrived at the bold art design led by Lead Art Director Keita Sakai, and how Audio Director Shuichi Kobori helped blend an absolutely banging rock-and-roll soundtrack into the action-packed gameplay of Hi-Fi Rush.

We hope this small peek behind the curtain of game development will give you a deeper appreciation for the massive amount of work and dedication that goes into our favorite games. Please enjoy!

DEVELOPER PROFILES

Game Director John Johanas

John Johanas joined Tango Gameworks in 2010. His first official project was as a designer on the survival horror game, The Evil Within. As Game Director on Hi-Fi Rush, he was involved in planning out the entire IP from scratch, creating the characters, game mechanics, writing the story, and finding solutions to problems as they came along during this huge new challenge for the studio. Later, as the project moved further into production, he became focused on the creative direction of the project and writing the game’s script. He loves the ending track “Honestly” by Zwan, a song that he had on repeat when writing the script. “It just fit the vibe of the game I was hoping to make so well. I’m just glad we were able to license the track for the ending of the game as it works perfectly.”

Lead Programmer Yuji Nakamura

Yuji Nakamura has been working at Tango Gameworks since 2016, but one of the first games he ever worked on was Dragon Ball: Revenge of King Piccolo for the Nintendo Wii — his first game with Tango was The Evil Within 2. Hi-Fi Rush was his first experience working as lead programmer on a large-scale project. He was responsible for the management of programmers on the application side, overseeing the quality of the gameplay for the controllable characters and battles, direction and the production of the UI, data deadline management, and more. His favorite track from Hi-Fi Rush is “1,000,000” by Nine Inch Nails. “It was used for the first boss, which I worked on to some extent, and it’s the song I heard the most.”

Lead Art Director Keita Sakai

One of the first games Keita Sakai worked on was The Wonderful 101 from Platinum Games. After joining Tango Gameworks 10 years ago, his first project was The Evil Within. While he has been working in the video game industry for 13 years now, before that he worked on background art for anime for over a decade on such projects as “Cyborg 009,” “Astro Boy,” “Stand Alone Complex,” “Macross 0,” “Tekkonkinkreet,” and “Sword of the Stranger.” For Hi-Fi Rush he worked on designing all things that were art related, which tapped into his experience in anime. He was responsible for the creation of the art for the overall world and universe, like concept art, designs, and lighting as well as the direction and task management related to art. His favorite song from Hi-Fi Rush is “Lonely Boy” by The Black Keys. “When the opening begins, my 6-year-old and 2-year-old kids start dancing around and get all rowdy. My son also loves it so much I hear him humming it.”

Audio Director Shuichi Kobori

Shuichi Kobori’s first game was working on the classic Square game, Chocobo Racing. When he joined Tango Gameworks 11 years ago, his first project was The Evil Within. What was notable about Hi-Fi Rush is that he was able to work on the project from the very beginning, from scratch, to help make a new IP. He was responsible for the content and quality of all things related to sound, such as music, sound effects, and voiceovers, and for the quality of the experience where the music and gameplay are closely tied together. While he loves all the music from Hi-Fi Rush, his favorite is “Whirring” from The Joy Formidable, “because of the way it connects to the story and creates a very emotional feel.”

THE BEGINNINGS

It’s one of those ideas that you would say when drunk and then that’s it, you wouldn’t do anything with it.

It’s one of those ideas that you would say when drunk and then that’s it, you wouldn’t do anything with it. We were trying to figure out the date where I randomly would just come over to someone and say, “You know what would be cool… fighting to the music, or something.” And then I’d just walk away, and they were like, “That was weird, and I didn’t know what you were talking about.” It must have been, I want to say, 10 years ago or something where I had this general idea.

Everyone was kind of watching him create a new concept, and it turned into a concept that Mikami-san liked and said, “OK, let’s make that.” But [at that point] everybody was already kind of shifted development-wise onto Ghostwire: Tokyo. Me included. Mikami-san called me over into his office one day and said, “Hey, do you want to help out on this?”

At the time I heard about Hi-Fi Rush being submitted amongst other concepts, I thought that this was the one that Tango would not choose. I thought it was a joke and I was surprised that it got chosen [laughs]. When that happened, I learned that I need to be humble. Because as Nakamura-San and John started to work on it — I could see them working hard on it – I learned that it was not a joke, and this is something that [needed] to be taken seriously.

When I heard it was more of an action game than a rhythm game… at the time, personally, wanted to make a new action game. So, for me, I felt, “Hey, this is a chance for me to work on something new, a new type of action game that I wanted to do.” It fell in that range of things that I wanted to do next, and the initial documentation didn’t portray Hi-Fi Rush as a dark-colored game; Evil Within and Ghostwire are a little bit darker in color and this one… I wouldn’t say [the prototype] was as bright as it ended up being, but it was completely a different color, and it was not as dark. And I saw that as a good thing, I wanted to work on something new and different and so it also fell within that range of things that I wanted to work on.

At the time, there were basically two pitch meetings. One was to the studio head, Mikami-san, and we needed to make sure he was cool with it before we showed it to the publisher [Bethesda].

So, the initial pitch meeting was not to Bethesda. It was internally within our company. I pitched it to my boss and I’m trying to think who else was in the room. I think our executive producer on the Bethesda side, Colin Mack, was there as well, taking pitches for what be developed in tandem with Ghostwire: Tokyo. So, I pitched the idea.

I had about a 10-page document. But the high-level pitch was basically an action game where everything that you do matches with the music and creates a living soundtrack. That’s kind of the elevator pitch right there. And then I went into detail:

“OK, so you’re going to be this defect who gets a robotic arm with their music player placed in their chest. And then they’re being hunted down by the company. And you must take out the bosses one by one. So, it’s kind of very meta in that sense, and very easy to understand. So, we don’t have to worry about storytelling. It’s more about these fun and interesting characters, and it’s going to be cartoony and over the top and self-aware, but just an emphasis on fun.”

It was something that I think everyone thought sounded cool. No one turned away like, “That’s stupid, that sounds dumb.” Probably because I pressed it as being, “I know it’s stupid, and it’s self-aware and we’re going to play with that. And it’s going to be fun because of that.” So, everyone saw that as being a great idea and they like the idea of music and action together because I think everyone just understands that that’s a good combination of things.

I was very anxious at the time going into that meeting because I wasn’t sure if it was good enough, and I was very nervous that this might be the end of the project. But it turned out that the reactions were really good, and the next step was to polish it up so that it’s presentable in a more publisher-friendly way.

But obviously, the same reaction came that I expected, which was “I don’t think Bethesda is going to go for this. We’ve never done something like this before, so, that’s going to be a hard sell.” And so, there was an interest, but how it sounds on paper it seems like a good idea, but is it really going to work out? Like, “Can you guys do it? You’ve only done horror games…”

When I got called in and [the concept was explained], I felt honored that I was chosen. But the thing is, the concept itself was really kind of easy to understand — it was a rhythm and action game that felt good in a unique way. From the documentation, and the verbal explanation, I was able to understand that mentally and I could also tell from that explanation that we needed a prototype to prove this out.

Because we liked the idea, we decided to make the smallest team possible, and see if we can make something [to show] not on paper, but a proof of concept. So, we went to prototype it, just myself and a programmer (Yuji Nakamura) for a year.

From there, the ball kept rolling and snowballing into a bigger thing, and we figured out what needed to be done to make it presentable to the publisher. And then once it was presented to the publisher, it just kept chugging forward, development kept chugging forward, and about four years later we have the game. But yeah, that initial pitch was the most nervous moment for me personally for this project.

BUILDING THE PROTOTYPE

I wasn’t really sure if I could actually make that.

We worked on the prototype for a year. We did get some help when we realized we needed it, like getting some animations in there or some visual effects. But for the most part, most of it was done by me and our lead programmer, Nakamura-san, and we did a lot of trial and error, but we did finally nail on what the core concept was.

John came to me, asking if he wanted to make a sound and action type of game, what kind of things would be needed for that? So, we brought in an audio programmer to help them understand. I thought back to my experience prior to joining Tango — I worked on some rhythm games in the past — and was able to talk to John about the challenges of making something like this. I realized quickly that what he had in mind would be different from the other kinds of rhythm games out there. But I could also tell what kind of challenges there were going to be, what the team would be facing, and the importance of the sound and music that would be chosen.

I could imagine in my mind what the game would be like, but I wasn’t really sure if I could actually make that. We had this initial concept document that John had created. And we tried to implement that into a game, or create a game prototype, of what was exactly in that concept document — that didn’t really go well. We spent about three months… two to three months… a lot of trial and error, just trying to reproduce what was in the document and it didn’t really work. And so, we had to come up with different things to try out — the fun on paper didn’t really translate well inside the prototype.

That turned out to be our biggest first challenge, that we needed to make sure that the fun we had in John’s mind be present in the prototype. What happened was that when we tried to recreate what was in the document to the letter, basically what happened was it turned out to be a very slow type of action game — we needed about three or four more months to figure out how to change that to be more fun. After about the fourth month, it started to click. It worked.

We were looking at videos recently and were like, “Wow, this is ridiculously unchanged from the concept.” It was essentially a 15-minute playable demo, which is extremely like the first level of the game, which is kind of a walkthrough where you learn the basics of what a light attack or what a heavy attack is. We had the basic four combos in there. We had the beat hits and the parry, and we had three enemy types: a regular enemy with the sword, a gunner enemy, and then a heavy.

It was very clear to me that John had something in his mind that he wanted to create, and he stuck to that vision from the very beginning, even though we kind of had to mold things differently. That trust really started to build because he didn’t change his thinking regarding what he was trying to achieve.

So, we had this demo that was 15 minutes long and kind of ended on this little teaser that we made at the end to show the further potential of the idea. And that was it, mostly for internal purposes. So, we played it internally. I showed it my [former] boss, Mikami-san, and he was like, “This is really, really cool. OK, we should figure out a way to get this in front of them [Bethesda] to present it properly.”

That prototype — and this is credit to Head of Production at Bethesda Todd Vaughn — he saw the prototype and basically decided to pass it around to a couple of people and say, “Hey, try this out,” and he didn’t say who it was from, because we didn’t have anything in this to say it was from Tango or anything like that. And internally, people were like, “This is awesome! What is this? I would buy this right now, whatever this is.” And so, by the time we went to pitch it [the second time], it had a viral internal hype behind it. People knew about it. So, we were going to pitch it and they’re like, “Oh yeah, everyone’s been talking about this. They say it’s amazing.”

I heard the reports through John that a lot of people have played [the prototype]. I was happy to hear that those people who played it really liked it. And John was extremely happy that it was received very well; I wasn’t really sure if people would like it, but it was at a level where we could show to the publisher, at least, and that gameplay experience of fun was definitely captured. It was good to make sure that the fun that we thought we created was fun to other people.

In a way, I think that prototype was, realistically, the way that this game got greenlit and got made. Because people from the beginning knew it was fun and it was fun to play. And people were just replaying that 15-minute demo over and over again.

Solving that [fun] problem was the biggest hurdle. If there were more people on the project at that time, it would have been much harder to do. So, it was a smart move to keep the project very small in the beginning.

It was really a game made for me. But if I think if this game is made for me, then there’s probably a lot of people who also will also resonate with this idea. I was confident that I wasn’t so outside the box that it was a weird game that would only sell for one person.

CREATING THE TEAM

All the people who were available had literally no experience making a game like this.

I didn’t really create the team. It was just the people who were available. And all the people who were available had literally no experience making a game like this. So, it’s not like, “I’m going to need him, and him, and him because they know how to do this and this and they’re going to make it happen.” It was, “Here’s what we want to do,” and everyone’s like, ‘I have no idea how to do this.’ Most of the first reactions were, “We don’t know how to do this; this is totally impossible.”

My initial reaction, when assigned to the team, was, “This looks like fun!” That was my honest impression at the time. But also, a big question mark was, “Can we make this?” I knew immediately this was going to be a challenge, but I saw it as a challenge that would be thrilling. I was excited about it as something to look forward to and there was some nervousness there, but it felt like we were going to go to some new playgrounds.

John and Nakamura-san were [the only] two people working on it and everybody else in the studio was working on Ghostwire: Tokyo, myself included. I was asked to help on it when I had time available, kind of like a part-time thing; to help when you can. But as we started seeing John and Nakamura-san iterating on their work, and being very creative, and seeing how they were improving on what they’d been creating, people tended to gravitate toward that creative excitement. The strength of the creativity there helped bring in a lot of people.

There were a lot of people on the team that didn’t have experience in creating games that utilized music like this. But since we had a prototype that worked, we were able to use that as the teaching tool… it made more sense than a lot of verbal explanation or other kind of documentation.

The prototype was key to the whole process. They would play the prototype and then we would be able to point out what was really important to the vision of the game. There were a lot of people like me who did not have much of a musical background and we had to get a common understanding of the key ingredients of a song… We would use the prototype to create a common terminology to use within the team to express different parts of the song and how those affect gameplay.

The core of the game is rhythm action. But as I talked to John initially — and John was very passionate about the rhythm action portion of the game — I was saying stuff like, “No, you must choose between rhythm or action. You can’t have both.” John kept saying, “It’s not one or the other, both are important,” and everybody said, “You must choose one,” and he’s like, “No, no, no, no, no, no.” It took a while before we were able to understand what he was really going after, but once we saw it, it dawned on us that John’s sensibilities to capture that so early on, in something that might be fun, was pretty amazing.

By utilizing measures of music and notes that would be key to the gameplay, I was able to use that to explain to the team through the prototype and to the new people who came on board.

People would bring in their own best work to help them out. And then because they’re so creative and we wanted to help them out, they would bring in their best work to put into their prototype. And then other people would see that awesome work that somebody else did, and then they’d say, “OK, I want to make sure I bring in something as good or even better,” right? So, the inspiration kind of like, fed off each other and then back in itself created this strong synergy of everybody trying to bring their best thing to the table to help them out. That’s still continuing today where people are bringing in new ideas for things on how to improve a project.

CONSTRUCTING THE SCORE

I wanted to capture the feeling of playing a guitar chord with a live band and that roughness to it.

Sound design was completely reversed [compared to a normal game]. The [sound team] normally would just come at the end to put sound over things, but here they had to be involved from the very beginning and figure out how things worked.

John had a very strong vision about having music lined up with each stage. For some stages he had a specific licensed song in mind to use. For stages that didn’t have licensed music assigned to them, he brought to the table some sample songs that he had in mind. Some of those were not actually rock songs, but we were able to listen to the Beats Per Minute (BPM) in that song and figured out what kind of vibe he was looking for, the instruments that were being used, and the general feeling of what he was going for by listening to the samples that he brought.

One thing that I was set on from the beginning was focusing on rock music and non-electronic music… I wanted to capture the feeling of playing a guitar chord with a live band and that roughness to it. Not like the perfect accuracy of a digital music track or something like that. And it just kind of fits for a brawler, that sort of rock feel. And I grew up listening to rock, which was more of a personal thing, but I just thought that it was a little weirdly unrepresented in the gameplay experience sense.

Yeah, John initially had this list of songs that he wanted to use. It was definitely rock-centric, late ’90s early ’00s — the kind of music he listened to while growing up. John mentioned this throughout the development of the game, that the songs he chose were of that era and the way he explained it was that the music is not very refined, but it is very strong in energy, and that those two things would fit very well with the story that he was trying to create and the feeling that he was going for — that it would bring the vibe to life inside the game itself.

I pushed for that, and the sound team initially came back, “What about just doing electronic music because it’s so much easier?” or “It’s going to be really hard to make tracks so people don’t get bored of rock music, because it’s just going to be rock music all over.” And so, I had to make these playlists and show that there’s all these sub-genres of rock that we can use and play around with, and I don’t think it’s going to be a problem. Because at the end of the day, if it’s good music it doesn’t matter and you’re playing the game and you’re not just listening to the music track the whole time.

For the battles and the levels, the music had to kind of match that groove of what the player experience is going to be. So, you’re walking through the stage, you have a battle here, you encounter some level gimmicks here, and so what he had in mind was where to start playing the intro music, where the verses would change, how the music would start building up and sometimes relax a little bit; a kind of emotional curve designed through the music.

And when he was explaining it, he drew a picture on a piece of paper showing what it would look like. He created a graph of how you proceed through the stage — you’ll encounter these things, and then the music will go like this and like that, for example.

We found by trial and error the BPM range that we’re like, “OK, gameplay in this range is fun and enjoyable.” I think it was about, 130 to about 160 BPM, and there is a significant difference if you play them back-to-back, but we can use that as sort of a way to gauge difficulty and feeling for different stages just by pure battle design. We would do it with a click track, and then we would come in and we’d make a stage and part of the stage prompts would be like, “This stage is going to feature this type of rock music,” and I would give a bunch of samples about the vibe that we’re going for. “And then for this stage we wanted difficulty increase, so we’re going to up the BPM to like 145 here.” So that’s how we scaled everything. But everything that we made was interpolated, so we didn’t have to redo animations. It was actually very easy to say like, “OK, let’s just do 145… click track… and then we’ll try it out to that.”

On the implementation side, once we figured out the general thinking there, we had two different challenges. One, for the use of licensed music, and the other for the use of making original songs for the stages.

On the licensed music side, the music already had beats lined up, the lyrics were already set, how many measures before things built up, how many measures of the different kinds of ‘ups and downs.’ Those were already set in stone.

When we would work with a licensed track, [I’d say], “This is the song… we don’t want to change the song. We don’t want it to make it feel like a remix of the song. We want to pay tribute to these licensed tracks that we’re using.”

So, we would take the track and basically pull it apart like piece by piece, like stem by stem, and say that there’s a guitar track here let’s coordinate this boss’s attack to that guitar riff, so it feels like they’re playing to that track. And time it so that it’s a four-phase fight that’s verse, chorus, verse, chorus, and when you defeat the first health bar it’ll then go into the chorus smoothly and escalate the fight. And we’d figure out what each track works individually and then see how we can incorporate that in the game and what worked best.

The thing is, players can control their character, right? So, in the game, the players have this freedom to move around. It’s up to them how quickly they want to go through a stage. Me and John really wanted to make it a seamless experience when you go into cut-scenes. So, there were some of those challenges around how we control that so that it feels seamless and not so jarring. So, we had to look for places within the music to allow for loops and for things to loop back to, to allow for that seamless experience.

We all wanted to avoid that jarring experience where you get into a location where the music stops and another piece of music starts, the unnaturalness in the middle of a lyric or middle of a word that could get cut off. We wanted to avoid that.

What we did was to make sure that programmatically we would find ways to know where the player is. If it was going to be a problem, we would know beforehand and we would lengthen the animation, or we would make the music loop a little bit, so it waits for a certain musical measure to happen when the player gets there.

For the original songs, since we were able to make the music internally, we were able to control a lot more what would be utilized for this. When talking to John, he had a lot of desire to make sure the player experience was good, but especially with the original songs because we have much more control over that. For example, having the player experience a guitar riff at a better moment at the start, or linking it to the gameplay itself. There were a lot of cool things we were able to play with.

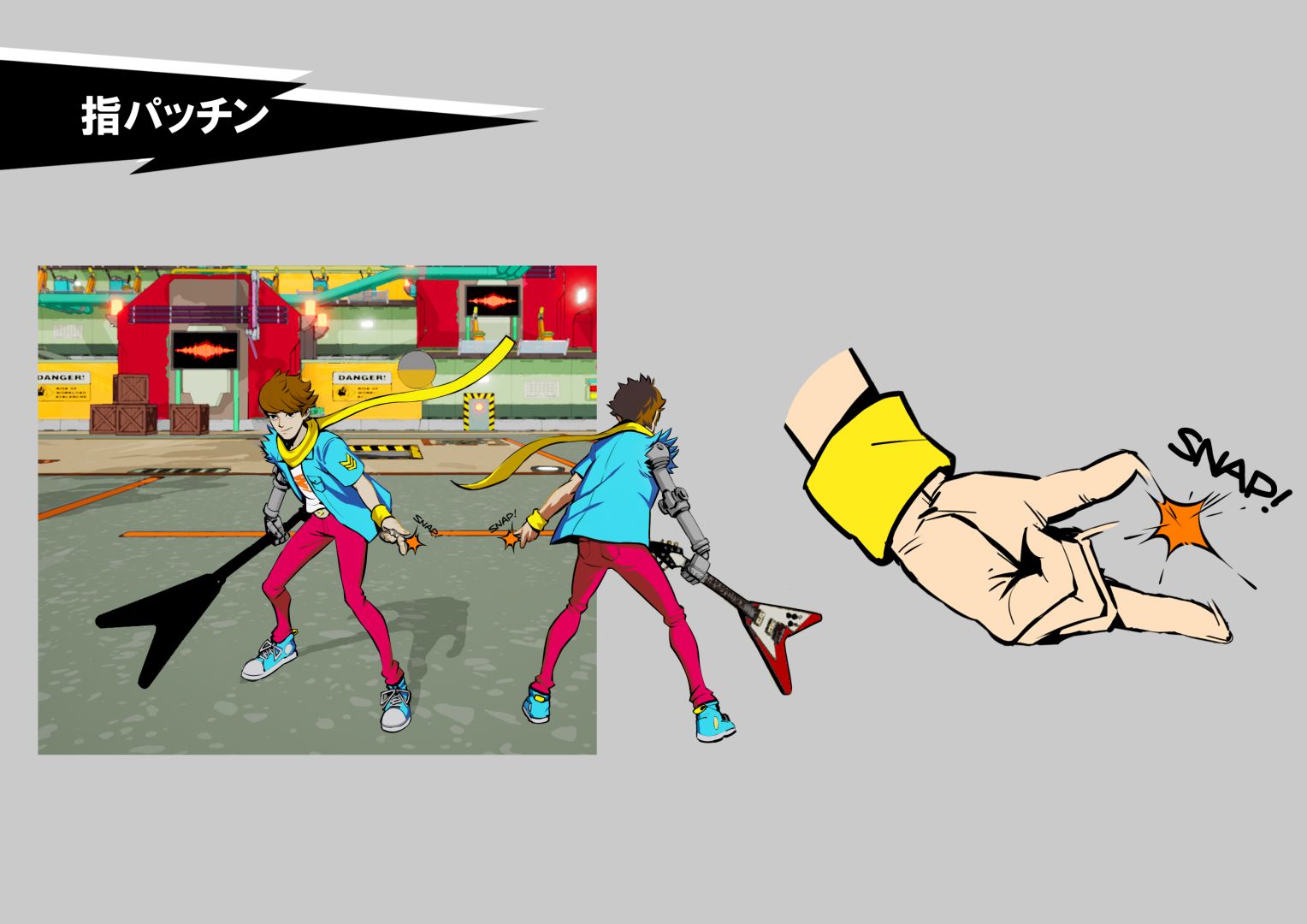

Everything was done in terms of beats, so every animation needed to fit, or every enemy’s attack needed to be like logically made from this attack that’s going to land in this rhythm. We have lots of very strict rules on everything, in that there wasn’t a sort of like, trial and error of guessing like, “There isn’t a music track so what do we do to make it work?” The logic was all there, it’s just kind of putting it all together.

And then when the music track came, from a combat standpoint, nothing really changed. The only thing that changed was when we’d make the music track, all the sound effects would need to be recreated for that music track. It could be in a different key and the musical stingers that come when you land like the combos and stuff, need to be made bespoke for that track.

It was a ton of storyboarding and documentation to figure out how to do that. I would say, much more complicated to making it feel like the track wasn’t being ruined and the player would also not be locked into something. That required a ton of work. But everything required a ton of work.

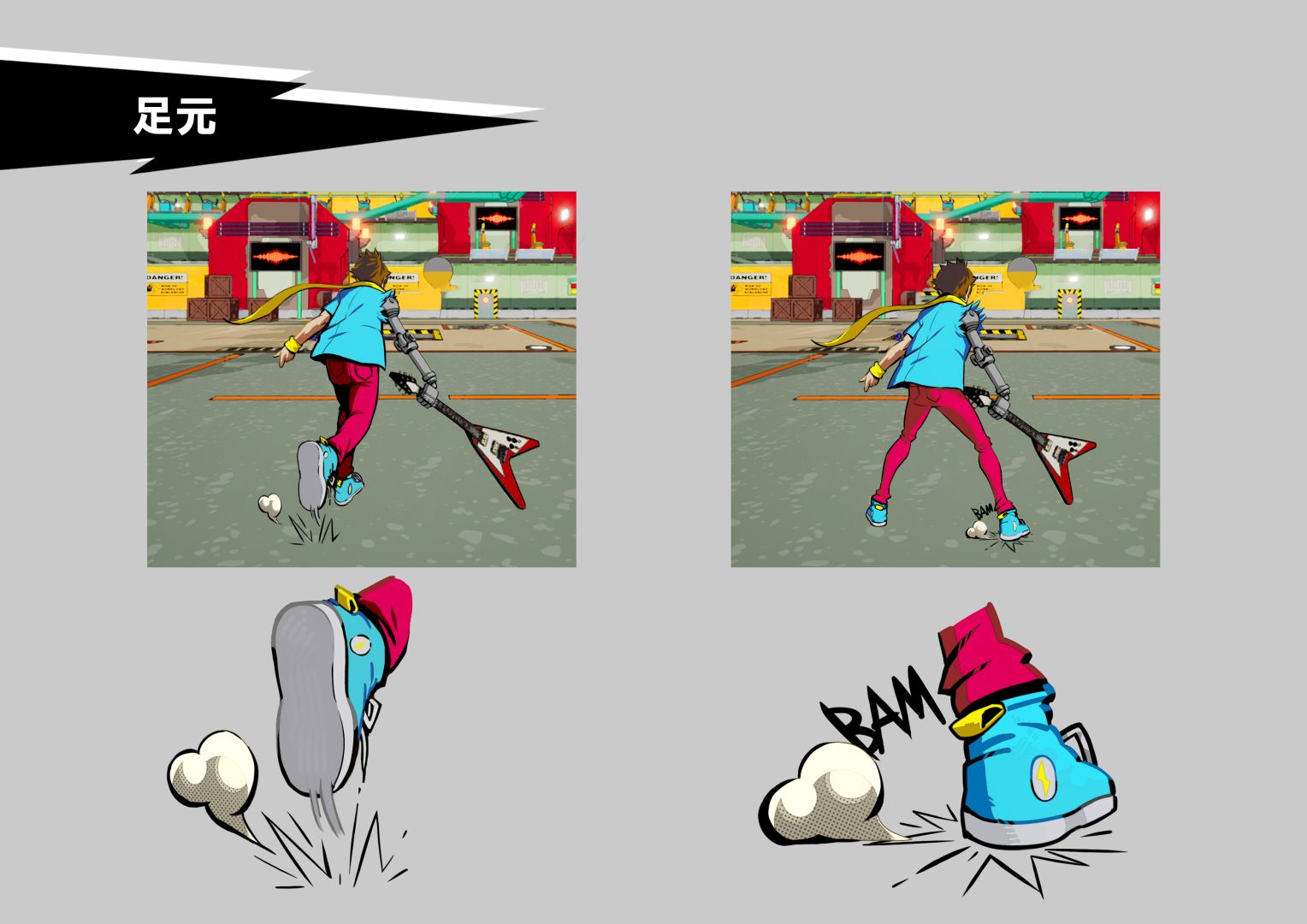

ART DIRECTION

Our game is ridiculous, it’s over the top, and it’s about music.

We were never considering anything realistic. That was a big thing I was down on. We had just made Evil Within 2 and we spent a lot of time working on realistic lighting and character models and stuff like that… but I was looking back at what are the games we remember the most. And I had this point in the pitch document where I said, “I want this to be a game that you remember,” that you’re not going to play it and then three months later forget that game came out.

All those games that came up were visually unique and not realistic looking. They played with art style, they played a lot with visual aesthetics to come up with their own identity. And so, on our pitch document, I put the ones that most people associate with Hi-Fi Rush, like Jet Set Radio, Viewtiful Joe, and Okami.

But we didn’t want to repeat what was done, so we didn’t say we wanted to just look like Jet Set Radio. So, what we did was this sort of 2D artwork, like what if a Japanese artist was asked to animate an American comic book but didn’t know anything about American comics — it should feel somewhere in-between that. Like, it doesn’t feel like a Japanese anime, but it doesn’t feel completely like an American made game.

This was a big pivotal moment in the development of the game — that really helped to solidify that vision of what we were trying to achieve. It took a lot of energy, and the colorful and clean look was achieved there — it went through a lot of iterations too, trying to realize that vibe of what John was saying about something that jumps out at you and has a fun feel to it.

Our game is ridiculous, it’s over the top, and it’s about music. There’s no reason why we should focus on realism — let’s go crazy with ideas as well, because you could do whatever you want and it’s like a comic book world.

The first initial look that we received is very different from what you know the final game is, but even at that point, I was able to tell that this is going to be different from everything else that we’ve seen — this does not look like anything that Tango has created before.

We had this 2D image, which is literally in the first part of the game. It’s where you first see the big Vandelay Tower, the V Tower, and in the distance you’re in this sort of production area. And everything had these keywords, this sort of colorful, sharp, and clean look. And especially when that first 2D image came out, we would put that up and say, “We should make the game look like this image.”

Initially we tried to create a normal or more serious-looking Vandelay Tower, but that didn’t really seem to be the right thing to do. We wanted to make it more iconic because it’s going to be a big central thing in the game. So, Vandelay starts with a V… if the tower was shaped as a V, it would be kind of fun. Let’s give that a shot and try to make that blend with the environment to make it pop and look a little silly.

Then we started thinking, “If this is a universe that accepts a building to look like that, what other kind of things would fit in that world?” So, this piece of art really helped us in the creation of the game.

That’s how we came up with the initial concept of the general art style, and then we just kept iterating on it to get it to add all these small touches that you see in the final game. Whether it’s the way the shadows fall and converting it to 2D animation and things like that but, we had this first image very early on and that was our key visual. We literally said that whatever we do, replicate this. Even use perspective things to make it look exactly like this. It just must look like this, and we’ll figure out the rest later.

GAMEPLAY

If that’s how you want to play, we’re going to allow you to play like that.

We wanted the game to be easy to play, hard to master, and we learned very early on that you should never start with the hard-to-master part; just make it easy to play. And one of the first things we got was like, “Hey, I could just spam the Light Attack button and get through all the battles.” Yeah, you can do that, but you’re not going to get that high rank at the end. And at the end of the day, is that how you want to play? If that’s how you want to play, we’re going to allow you to play like that. Early on the team was worried, (because) you don’t need to use all these combos. And I was like, “Yeah, you don’t. But we’re going to balance it so you’re going to want to.”

His vision for the game was very strongly expressed as action game 70%, rhythm game 30%. A 70/30 mix. But as new people came in and played the prototype, and they started thinking that it might be better to have a higher percentage of the rhythm game, John would stick to his vision and constantly explain, “No, no, no. It is a game where action is 70% and rhythm is 30%.” That was something that he said multiple times through the project.

You’re afraid that people would get into a groove and just use the same things. But as we were ending development, we were casually talking about [combat] like, “Oh, I use this attack on this, and this was more effective.” And others were like, “Oh, I never used that attack! I always use this one.” And so, people kind of found their own niche that they played in. And I was like, “OK, that’s exactly what we’re going for to begin with.”

We followed a mantra: No matter what we do, the game needs to feel rhythmical, but we can never sacrifice responsiveness and player freedom. It was an extremely difficult thing to balance, and the way we did it was what you see in the final result, is that we support you whenever you press a button.

One of the earliest things that (the team) had said was that if you don’t press the button on beat, the player doesn’t attack; to show that you failed. And I was like “No, that just feels terrible.” What it should feel like, is while you’re playing the game, we sync it up so even if you’re not playing to the rhythm, you feel like you are — I think that was the key.

But in the end that was the reason why it feels good. Because we saw that in people’s responses. You don’t even have to be good at rhythm games to play this because we do the work for you. It’s kind of like an assist, but it doesn’t make you feel like you’re playing poorly. We saw that too, that people have been like, “I’ve never been able to do that in the other action games, but I’m able to do it in this one.”

THE DIRECTOR’S CHAIR

We had a clear identity of what this game was very early.

I was like, “Look, we’re making a game that’s like a rhythm action game.” People would say, “What if we take the rhythm part out of this part,” and I’m like, “No, no, we can’t do that.”

I was the level designer, battle designer, I did all the specs for the enemies and how the battle will work out, and I would give all the feedback for the music and animation, and I would dictate how the animation needs to be fixed and how the UI should look and things like that. And I wrote everything, and I had to implement how the dialog would play out with the characters.

He’s really the type of guy that didn’t want to bend his core vision. And I could tell by listening and watching him talk to other people, and others would come to him with ideas, and sometimes those ideas would help that for vision; sometimes they wouldn’t. But he would listen, and I would see him struggling internally, trying to find ways to make it so that those other ideas could still live without having to change that core vision.

Yeah, he had a lot of images in his mind that he wanted to convey to the team for various parts of the game. For many, many parts of that game. But yeah, his hands were on so many different things and he wanted to comment on everything, or touch everything. It created a situation where he himself might get, you know, overflooded with too many things to do.

There was a department head in Hi-Fi Rush that really fits this description. One could say that John was kind of like Zanzo (laughs).

I think I was very firm, in a strict sense. I needed to make sure that the first version of the game that we made was exactly to spec of what it needed to be. Because I’ve seen that if you have a vague first version of the game, it just kind of shakes and falls off the rails later in development when people are not sure what it’s supposed to be. We had a clear identity of what this game was very early.

Some people might take that as stubborn. Others might take that as somebody who’s confident with his vision, who wants to realize that vision. And I felt like I could trust him a lot more because I saw him do that. Here was something that he was willing to really stick to his guns to, that he strongly believed in, and that was something that I wanted to support. So that was how our relationship kind of grew to becoming a very trusting relationship.

Everybody was inspired by the good work of each other. And that good synergy was there; we all wanted to make a good, awesome game. Because of that love and desire, we could see what John was trying to achieve. If he came to the table with something that was too large to achieve, we would be able to take that essence of what he was thinking and create a counterproposal to what he was trying to do and find ways to still get what he wants, but in a more manageable way.

DEVELOPMENT

This ain’t no indie game.

It was supposed to be a small project from Tango. And people probably see it as this weird, sort-of AA title. Or people are like, “Oh, they made a nice indie game.” This ain’t no indie game. Obviously, I can’t say how much it cost, but it was not a cheap game to make.

For the first two years I would say it was a small project. But what John wanted to make was not a very small thing to do. We needed to get more and more people to help. In my mind, small projects would be maybe 20 to 30 people for two years. We ended up developing for about five; I wouldn’t call it a small project at all.

I saw all the tasks that went into it, and those tasks were huge. I would never call it a small project. Maybe if you look at things from a budget perspective, or relatively speaking to a higher budget game, you might have a different view. But from my perspective, I worked on it and I’ve seen the amount of tasks that had to go into creating it.

The game had a lot of people wearing multiple hats. I probably took on way too much doing that. But later, obviously, once the team was built out, I stepped back, and I would always do these level briefs. I would chart out what this level is about — and then then pass it over to the level designer. Because I knew we were doing something that was so different, it needed to be calculated so strongly, that I would come back in and we’d go through the level and make sure that everything was to the beat.

People who joined the team towards the end or towards the middle of the project had a different mindset. Like, “This game might be better if there was a more of a rhythm aspect to it.” I talked earlier about our action 70%, rhythm 30% split, and they (new team members) wanted to change that ratio around a little bit so that the rhythm aspect would be a higher number. And they would find ways of trying to introduce that into the game without mentioning it to everybody else, so things might creep into the game like that we had to prevent that from happening.

The leads would meet up and John would explain very strongly to the group again that the game is 70/30 and if he starts seeing anybody say something else than that, or if he sees somebody else trying to create a feature that doesn’t really represent that, then we should probably realign ourselves again and try to make sure that doesn’t happen.

Not everyone on the team was musically trained or familiar with some of these aspects. Like, a battle needs to always start at the beginning of a measure and I’m like, “Nope, it’s starting on beat three. You need to redo this because it is not working.” So, I would comb over the levels and pick apart everything. If I feel like there’s not enough stuff moving in a battle, we would need to make sure people see moving things.

Some moments in the game we wanted to make sure that the lyrics matched the gameplay. One song that was the most difficult to work with was Number Girl’s “Inazawa Chainsaw,” when Chai was using a magnet to get on these rails to evade the attacks of Kale. This was one where John specifically had in his mind regarding what kind of gameplay would occur when specific lyrics played in the song. It was a perfect utilization because the music is very fast, it’s got a high BPM (Beat Per Minute), it’s got these really harsh drums that start playing, but it also has a very live performance feel to it, which means it’s not a perfectly calculated BPM when you actually look at it in a computer.

We had a lot of retakes. A lot. Like, over everything. Even for the environment team. We have these boxes that you can break in the game, the sort of wooden-looking boxes. I want to say we made like 100 versions of that. That was one of the first props we made to figure out how much detail should go into a prop in the game.

We tried out many different iterations and it turned out to be very tough to articulate. That’s when I realized that for a lot of this stuff, I’m going to have to create a lot of artwork to communicate through. We had to kind of create some artwork to make everybody feel like, “This is what is and it’s OK to look like this,” which helped make everybody feel a little bit more comfortable about how a toon shaded game is made. There was a lot of learning that needed to be done, or unlearning might be the right word, but a desire to change.

Most of the artists on the team came from within Tango, which has been known as a studio that makes more realistic looking games. Some of those artists would be thinking about like, “Can we add more gradation, or can we dirty it up a little bit so that it looks more interesting when that happens?”

You can tell with the production values; it’s very polished. And we had a lot of time to work on it. If you look at the staff list at the end, we didn’t have a lot of people, but it was made by a smaller scale team for a long time until the final sprint to pull people in to get it finished. Which worked in the game’s favor. I think it’s a smart way to make something that doesn’t require like 1,000 people to make a game. But to make anything that’s new and challenging… start with a small group of people. Because you’re less likely to lose a cohesive vision with the smaller group.

Looking back, it was a big project for the studio because it helped create this vibe that we can create something else, you know? That we can create different kinds of games that players can love. And that confidence building and image building, when I look at it that way, it was a big project. It was a big project for Tango.

THE “SHADOW DROP” RELEASE

Every goal that we were trying to hit, we were hitting.

The shadow drop wasn’t the initial plan, but we did want a very short campaign. The idea that it was so different than anything we’ve done before, we wanted that to catch people by surprise. I think, realistically, we wanted something like 3 months. We would announce it, surprise people, and then say it’s coming out very soon.

But then we just could not find a good time to make it feel like it wouldn’t get overshadowed by anything else, especially in our release period — if you want to market something towards the end of the year, you get swallowed up the Christmas marketing and all those releases.

But then this Developer_Direct idea came up, where there’s a small group of titles that people already know exist, and then we can have that be a standout surprise, which then turned into making it available at that point.

It was the first time for us – I had never done a shadow drop launch, it was my first experience. I don’t know if anybody else had that kind of experience, but for me it was a very thrilling experience in that regard.

I wasn’t able to tell my friends and my family what I was working on. But, because of the shadow drop, it added an element of surprise to the customers liking the game, because of the way it was shown and announced and released at the same time. It probably added to the mystique around it, the intrigue.

So, the game is coming out and we’re watching the initial reactions. We’re seeing people slightly skeptical, but then it’s available now and they’re excited. They play it right away, and they’re getting blown away by the polish of it.

And then they’re like, “Well, this is like good!” and “I’m on stage three and it’s just like getting better!” and “Holy crap, what is going on with this?” People were responding and they’re saying the exact same things that we had on our sheet, like literally in the pitch document. “It’s like a moving cartoon,” or “It feels like I’m part of the soundtrack,” or “It’s like a music video,” or “I’m not even good at rhythm games but I feel like I’m playing to the beat.” People are just literally repeating the things we had, on what we wanted people to say.

I didn’t realize that this is the kind of game that is best explained by actually having the person play the game rather than, you know, presenting or explaining game features. In this case, you know, it made sense to me that, you know, this would be best presented in a… what do you call it… get it in front of me, get the playable in front of the customers as soon as possible fashion.

It also helped me feel a little bit nostalgic. Like, back when you’re younger and if there was a game you liked and you knew it was coming out, I would withhold information about that game from myself by not looking at the articles in game magazines and keep all the surprises for when I finally got the game in my hands. Nowadays it’s harder to do that with information just everywhere. But the shadow drop I was able to kind of do that, because there was no information about that game and when it came out, it was all a lovely surprise, because you don’t have any information of that ad campaign and so there was that kind of strangely nostalgic feel to it.

And that was also what people said when they were finishing the game. They’re like, “This restored my faith that you can have a fun video game.” And that was our pitch from the beginning: It’s just fun. You know? Like, remember when video games were fun type things? Not like these deep, engrossing stories that made you cry, or made you reevaluate whether you were an actual human in this society that we live in. It was just supposed to be this fun story. There is some depth to it that you can take away from it, but realistically, it’s just supposed to be about having a good time.

WHAT’S NEXT FOR TANGO Gameworks?

I think that makes us better as developers, because we get to try new things.

The positive reaction is that I think it (Hi-Fi Rush) did what we wanted it to do, which is to show that we were not just a studio that can only make horror games. Looking to the future, I think if we can do something like this, we’re now a studio that’s very malleable for whatever project I think we can take on. And to show that we can, if we do it, we put the effort into doing it. We don’t cop out on trying it. So, I like to think that we kind of finally achieved our goal of not being pigeonholed into one style.

Looking back, when I looked at the team, there were people who came to Tango wanting to make realistic looking games, that darker themed or horror type of games. And when they got the position to make Hi-Fi Rush, they weren’t thinking at as a positive thing, like “Oh my God, I have to work on this?”

But as they got to know the game and as they got into the groove of development, they started to notice that it’s fun to make something that is fun.

I think that makes us better as developers, because we get to try new things. It’s better for gamers because they get to try new experiences that developers want to create.

With Hi-Fi Rush, we were able to prove to ourselves that it is possible to be able to do something really [different]… I think, yes, it changed the attitude at the studio.

Being a studio that is kind of been labeled as “horror only” is something that we wanted to grow out of. It’s something that we’re definitely good at… but we see this as a new challenge.

From my view, Tango always had a lot of freedom. There’s a lot of things that we were creating that were not seen publicly, and so I personally had a lot of confidence in that freedom that was going on here. It’s just that with Hi-Fi Rush, since it actually got released, that has changed the public’s view of Tango, right?

Everybody here has now gained that experience of making a non-horror genre game, meaning that we can make other genres. And that confidence has definitely been built up within the studio. It changed the attitude of people here and in regards to like “Hey, what else can we make?” We can challenge ourselves to make something new that is not what the older themes of what Tango used to be.

So, we’re looking forward to what we can do in the future. We’re not sure what that is yet, but it has created this new attitude of like, let’s look forward and what new challenges can we challenge ourselves to.

Hi-Fi RUSH

Bethesda Softworks

Hi-Fi RUSH Deluxe Edition

Bethesda Softworks